Layr curated by Nick Irvin

„Dowsing“

www.emanuellayr.com

Curator(s):

Artist(s):

- Julie Becker

- Gene Beery

- Whitney Claflin

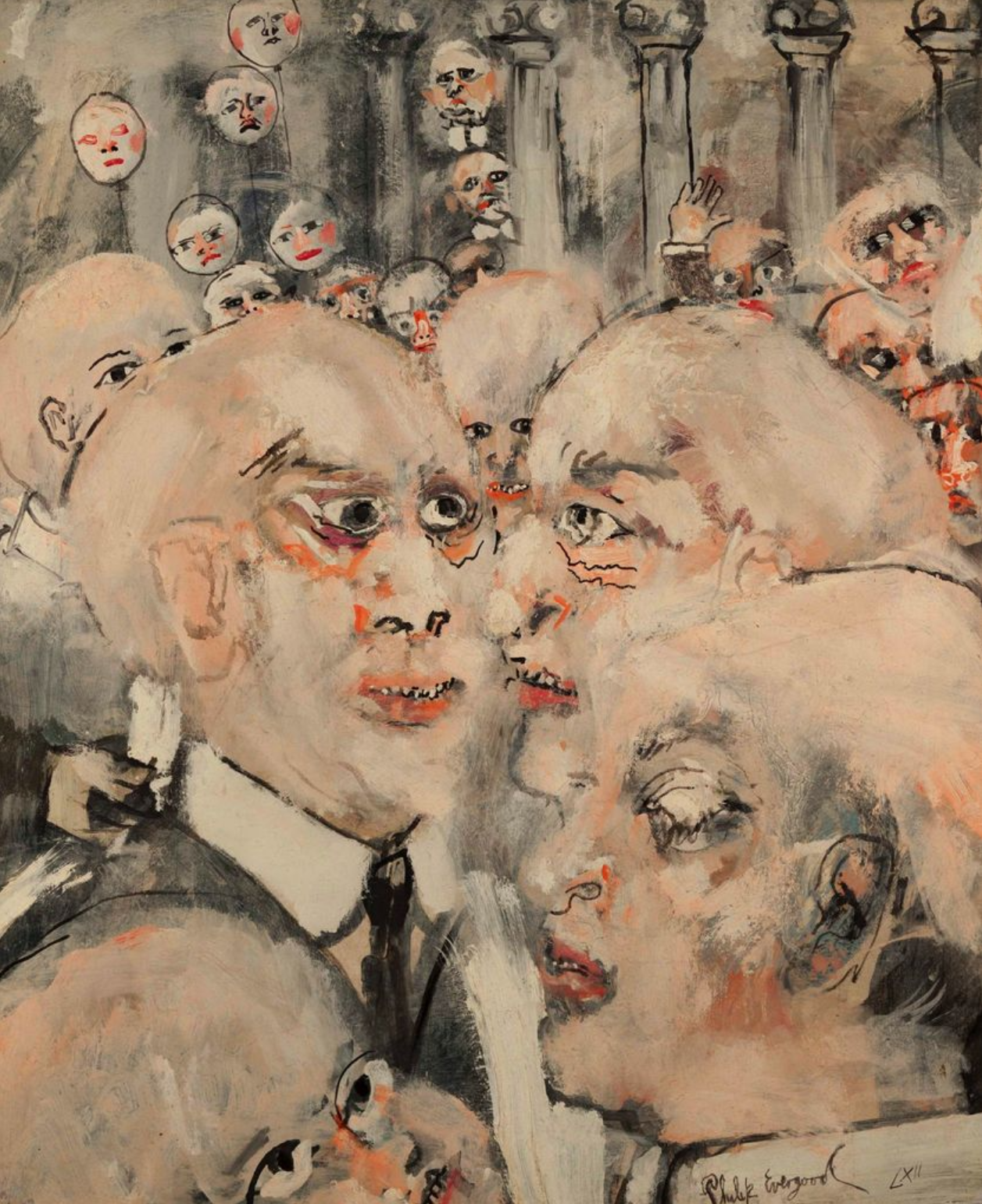

- Philip Evergood

- Hollis Frampton and Marion Faller

- Stano Filko

- William Gropper

- Jeff Joyal

- Donna Kossy / Kooks Archive

- Lee „Scratch“ Perry

- Ben Sakoguchi

- Frances Stark

- SoiL Thornton

- George Kuchar

- Joe Potts

- Mathias Groebel

Exhibition text

More

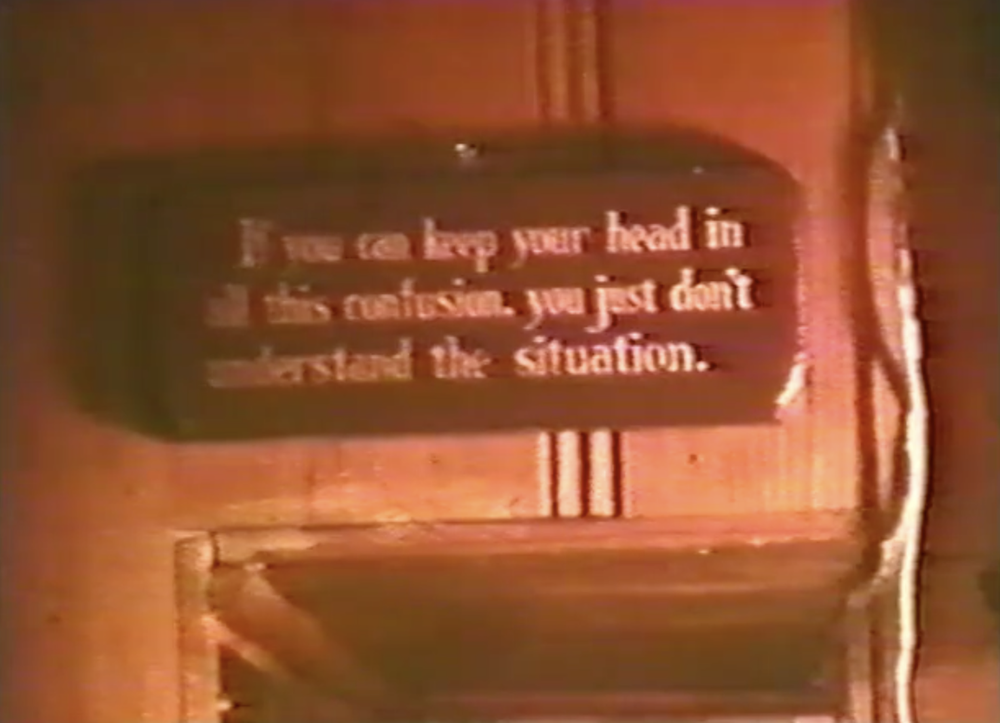

Our heads hurt. There’s so much news, and too many reactions to it. By now, “information overload” appears less of a revelatory concept than the obvious state of things. We point it out like one points out the weather; we manage its effects with metaphors of diet and addiction. Tuning out is one popular means of self-preservation. If you want to keep your head on straight, it’s best not to look too hard.

This exhibition gathers practices which decline to turn away from the heady task of sensemaking in an overly complex, media-saturated world. Instead, they hold on to the urge to distill from that frothy saturation some grasp of the big picture, the whole. Rejecting the offer to tune out, perhaps against better judgment, they dive deeper in, voracious, until they arrive at some baffling conclusion. I like to call this info-lust: the hoarding and arrangement of signals, no matter how disparate, no matter their bulk. There’s a resemblance to science here, but that’s mostly a pantomime (and why not – wasn’t it reason that landed us here in the first place?). At its core, the tendency instead favors fever and reverie: a controlled chaos, meticulously assembled.

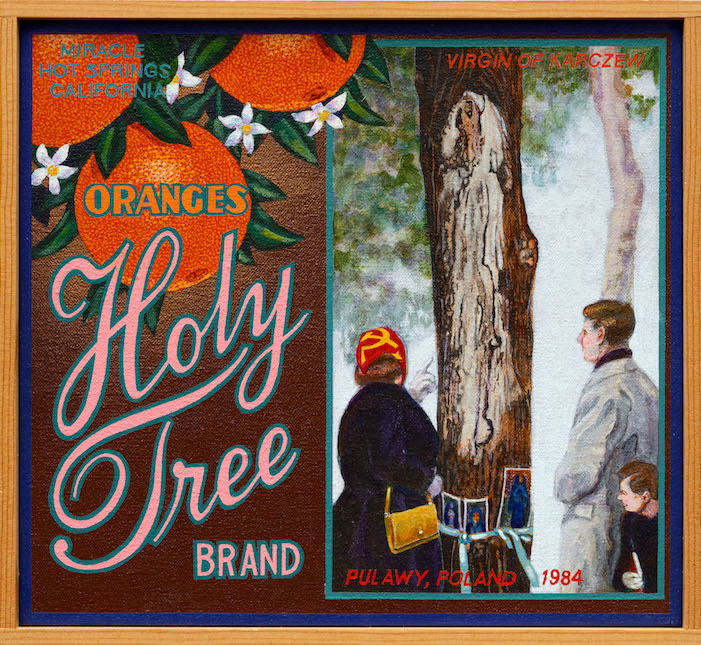

Clearly, we’re in the realm of paranoia, or more precisely, pareidolia: interpretation run off the rails.

Homespun fringe beliefs were once a curious sideshow to the rationalist mainstream consensus of the twentieth century. Those poles have collapsed into more of a tight, brittle knot in the twenty-first. But when the center still held, belief found sympathetic expression in the periphery, among countercultures, dissidents, avant-gardes, and other truth-seekers. But these communities were rarely 100% tuned out, no matter how hermetic. Counterculture needs a culture to counter, and the term ‘fringe’ itself implies a central fabric from which it hangs. From today’s vantage, when alternatives get absorbed before they have even articulated themselves, there’s something quaint, even nostalgic in the clarity of this dialectic. How bounded the mainstream was, even thirty years ago. How nice that the possibility of an outside, an otherwise, was once so evident.

“Homespun” is important. There’s something folksy, egalitarian, and fundamentally uncredentialed about fringe thinking, and that is part of its threat. Fredric Jameson, with some condescension, called the conspiracy theory “a poor person’s cognitive mapping […] it is a degraded figure of the total logic of late capital, a desperate attempt to represent the latter’s system.”[1] For Jameson, conspiracy thinking is the vocation most available to a curious and restless mind deprived of more proper outlets – though he remains vague on what those other outlets might be. One could argue that Jameson’s is a distinction without a difference: poor or rich, credentialed or not, the task of representing the unrepresentable system, of pinning down the absent cause, leads regardless into the same strange space beyond categories, beyond reason, and beyond good taste. The toll of that space will drain you either way. Despite that cost, some still can’t shake the countercultural axiom that “just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not after you.” Henry Kissinger put it more bluntly: “even a paranoid can have enemies” – and if anyone could confirm whether paranoids have enemies, it’s him.

Dowsing is the folk practice where a forked stick is used to detect veins of water or rare minerals hidden deep within the earth. It is medieval in tenor, but older than that. Dowsing has been repeatedly debunked, yet the practice still persists, perhaps because it is sometimes still correct: even a broken clock is right twice a day. Similarly, a disreputable paranoiac might still be on to some kernel of truth amidst all the noise. Werner Herzog calls the object of such pursuits “ecstatic truth.” In defining it, he quotes Gide: “I’m modifying facts in such a degree that they resemble truth more than reality.”[2]

It’s messy turf, and no doubt contentious. Increasingly it is potent and, consequently, policed. An inconvenient truth – even if it is more empirical than “ecstatic” – can easily be dismissed for the illegitimacy of its advocates. When Enlightenment scientists tried to eliminate dowsing and other traditional superstitions from the Mining Academies, superstition held on more doggedly than they could have expected. They found that the traditional miners’ pseudoscience was interlaced with generations experiential knowledge among the facts of the land.[3]

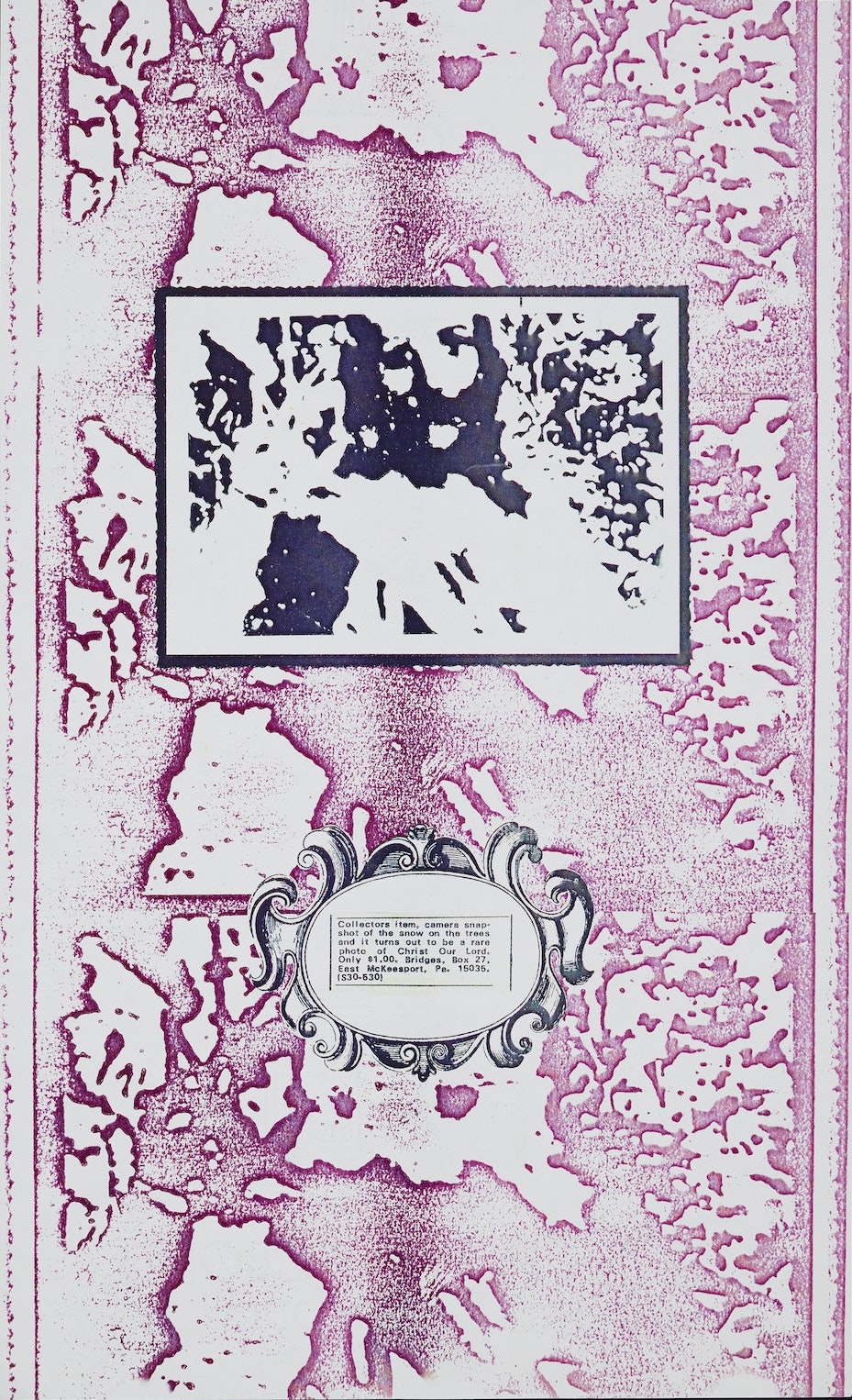

One self-authorized expert on modern fringe thinking is included in this exhibition. Donna Kossy is a writer and antiquarian based in Portland, Oregon, who specializes in what she likes to call “Kooks.” From 1988 to 1991 she published a zine by that name, which chronicled case studies from “the outer limits of human belief.” She wrote of cults, UFOlogists, flat-earthers and mad prophets, and along the way she collected their tracts, posters, and various xeroxed testaments. Some of these she re-xeroxed directly into the zine, and some of them are on view here.

Like most people interested in this stuff, Kossy does not believe what her subjects believe. But what’s more remarkable is the way that she approaches belief without irony or scorn. Like a folklorist, she has a fondness for the imagination, the energy of thought, the meticulous craftsmanship of these dense, lonely cosmologies. Beyond amusement, she identifies an epistemic merit to studying the fringe: “By documenting lives and ideas that might otherwise be lost in the onrushing tide of the dominant paradigm, we may be able to examine the process by which an idea comes to marshal its forces. Perhaps we will come to appreciate the subtleties and gradations of human inspiration. In addition, we may be able to overcome an ingrained xenophobia of the mind.”[4] In effect, she is describing the merits of art.

But the QAnon era has given even Kossy pause: in a more recent article, she grapples with the historicity of her own project, and marvels at the new century’s mainstreaming of conspiracy culture.[5] Yesterday’s cranks are today’s pundits. They no longer require a connoisseur to exhume them from their dusty PO Box, no zine to disperse their message. The stakes are a bit different now. Kooks no longer stay in their corners.

– Nick Irvin

[1] Fredric Jameson, “Cognitive Mapping,” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, ed. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, 1988, p. 356.

[2] Werner Herzog, “Minnesota Declaration: Truth and Fact in Documentary Cinema,” 1999. First distributed at Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota, on 30 April 1999.

[3] Warren Dym, “Scholars and Miners: Dowsing and the Freiberg Mining Academy,” Technology and Culture, Volume 49, Number 4, October 2008.

[4] Donna Kossy, “Introduction,” Kooks, p. 8.

[5] Donna Kossy, “Welcome to the Post-Kook Era.” Broken Pencil, July 28, 2021.