Galerie Krinzinger & Krinzinger Schottenfeld curated by Verena Formanek

„Where to now? | الى أين الآن؟“

www.galerie-krinzinger.at

Curator(s):

Verena Formanek studierte an der Universität für angewandte Kunst in Wien. 1989 Kuratorin für Design und Ausstellungen, 1993 stellvertretende Direktorin am MAK, Wien. 1996 bis 2004 stellvertretende künstlerische Direktorin der Fondation Beyeler, Basel. 2006 bis 2009 Leiterin der Sammlungen, Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich. 2010 - 2016 Senior Project Manager Guggenheim Abu Dhabi. Derzeit freischaffende Kuratorin. Aktuelles Projekt: Evaporating Suns, Contemporary myths from the Arabian Gulf for KBH.G, Kulturstiftung Basel H. Geiger

Artist(s):

-

Mohammed Kazem More

Mohammed Kazem (born 1969, Dubai) lives and works in Dubai. He has developed an artistic practice that encompasses video, photography and performance to find new ways of apprehending his environment and experiences. The foundations of his work are informed by his training as a musician, and Kazem is deeply engaged with developing processes that can render transient phenomena, such as sound and light, in tangible terms. Kazem was a member of the Emirates Fine Arts Society early in his career and is acknowledged as one of the 'Five', an informal group of Emirati artists – including Hassan Sharif (+2016), Abdullah Al Saadi, Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim and Hussain Sharif – at the vanguard of conceptual and interdisciplinary art practice. Often using or representing his own body in drawings, performances, and photographs, Kazem employs geographical markers as a way to locate his own subjectivity in relation to the rapid modernization and development of his homeland, the United Arab Emirates.

Since 1990, Kazem has created visual representations of sounds by vigorously scratching and gouging paper with scissors. “Scratches on Paper”, a series of works that range in size from sheets of writing paper to scrolls several meters long, is a set of labored silent scores that makes visible past movements and sounds. In his series “Photographs with Flags” (1997–2003), Kazem is pictured standing with his back to the camera alongside various flags that designate the spaces of urban expansion to come, bearing witness to a land on the verge of transformation. To make “Directions” (2002), Kazem tossed wooden panels inscribed with GPS coordinates for various UAE locations into the Arabian Sea, leaving them to float over geopolitical borders. The project was expanded a decade later in “Directions” (2005/13), an installation for the UAE Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale. Immersed in a wraparound video installation depicting the sea, the viewer is cast adrift with only a set of coordinates projected on the floor to aid orientation. Throughout his practice, Kazem’s photo-documentary techniques and insistence on measuring the world around him have been infused with a subtly romantic focus on individual position—be in it the Rückenfigur of “Photographs with Flags” or the visceral disorientation of “Directions”—pointing to his, and by extension a universal desire to be grounded.

-

Layla Juma More

Layla Juma (born 1977, Sharjah) is a multidisciplinary artist from the Emirates. An artist as well as architectural engineer, Layla is interested in compositions of visible and felt connections. Experimenting with abstract concepts and physical forms, she explores links between elements of being. Her work is often open-ended yet balanced, where each composition presents a layer of traced links.

A member of the Emirates Fine Arts Society since the early 2000s, Layla is among the third-generation of Emirati artists and takes inspiration from prolific UAE conceptual pioneers, including Hassan Sharif and Mohammed Kazem.

In 2021, Juma had a solo exhibition titled “Squaring the Circle” at Aisha Alabbar Gallery, Dubai, UAE. She participated in exhibitions in the UAE and internationally, including Layla Juma & Carolin Kropff, STUDIOSPACE Lange Strasse 31, Frankfurt, Germany (2023); “From Barcelona to Abu Dhabi: Works from the MACBA Art Collection in dialogue with the Emirates”, Manarat Al Saadiyat, Abu Dhabi (2018); “Portrait of a Nation”, Me Collectors Room, Berlin, Germany (2017); “There Are Too Many Walls But Not Enough Bridges”, Kunst (Zeug) Haus, Rapperswil-Jona, Switzerland (2015); “Emirati Expressions III: Realised”, Manarat Al Saadiyat, Abu Dhabi, UAE (2014); “Mind - Dubai Contemporary”, DUCTAC’s Gallery of Light, Dubai, UAE (2012); Singapore Biennial (2008); and Cairo Biennial (2006). Her works are in several collections in the UAE, including ADMAF, Environment Agency, Al Dar Hotel & Hospitality, and the Ministry of Presidential Affairs in Abu Dhabi; Barjeel Art Foundation, and Sharjah Child Friendly Office in Sharjah; JP Morgan Chase Bank in Dubai; and internationally in Art Towada Center, in Aomori, Japan.

-

Lamya Gargash More

Emirati artist Lamya Gargash was born in 1982. After graduating from the American University of Sharjah in 2004, she moved to London to pursue a postgraduate degree in Communication Design from Central Saint Martins. Gargash is heavily inspired by inhabited and abandoned spaces as well as cultural heritage in a context of rapid change. Exploring modernity, mortality, identity and the banal, Gargash captures the beauty of human trace and the value of the mundane. Many of Gargash’s works depict interiors. Selecting spaces that have been semi-abandoned by homeowners seeking to upgrade, the artist documents the moment of transition lost to others in the speed of departure. The somewhat eerie images pose questions about the need for renewal and inherent nomadism. Taking visual cues from interior decoration, theatre and museum exhibits, Gargash creates works that layer anxiety, nostalgia and restlessness. In her recent works, Gargash has turned her camera upon ethnographic artifacts from the Al Ain Museum in Abu Dhabi. The ancient objects are everyday domestic items that are nevertheless anthropologically important. No longer hidden from view as they undergo restoration, Gargash reframes them and chronicles their history in a personal and poetic manner whilst highlighting the remnants of human presence.

Gargash was selected to represent the UAE in its debut pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2009 where she showcased her “Familial series”. In the same year, she also participated in the 9th Sharjah Biennial in Sharjah, UAE with her “Majlis series”. She participated in several film festivals such as; Locarno Film Festival, Switzerland; Osaka Film Festival, Japan; Amsterdam Arab Film Festival, Netherlands; Paris Arab Film Festival, France and Dubai International Film Festival, UAE. Throughout her career Lamya has won a number of awards for her work in film and photography. In 2004, Lamya received first prize in the Emirates Film Festival, as well as Ibdaa Special Jury Award for her movie titled, Wet Tiles.

-

Kader Attia More

Born in 1970 in Dugny, France, and raised in suburban Paris and Algeria, Kader Attia earned degrees from the École Supérieure des Arts Appliqués Duperré, Paris, in 1993; and École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, in 1998.

Attia’s binational background informs a practice that reflects on prevailing differences between contemporary cultures and aesthetics, and on the impact of dominant Western societies on their former colonial counterparts in the context of a globalized world. In installations, photographs, and videos, Attia focuses on the liminal zones that separate contrasting sensibilities, and on attempts to close these gaps. Much of his research has been centered on the concept of repair, which he regards as a human constant envisioned in opposing ways by Western modernists and Eastern traditionalists. Attia regards as erroneous the notion that humankind invents objects, environments, or situations, as opposed to simply repairing—or adapting—existing models.

Attia’s photographic series “Rochers Carrés” (Square rocks, 2008) presents young Algerians seated on large concrete blocks at a local beach, gazing out to sea in the direction of an unseen Europe. The blocks evoke the Brutalist apartment buildings of the troubled immigrant banlieues, or suburbs, in Paris where the artist grew up, while the figures’ contemplative postures suggest the desire for a better life across the Mediterranean. For his installation “Untitled” (Ghardaïa) (2009), Attia modeled the Algerian town of the title in couscous, a regional staple now popular worldwide, accompanying the fragile construction with photographs of architects Le Corbusier and Fernand Pouillon and a copy of a UNESCO declaration that identifies the town as a World Heritage Site. Ghardaïa was colonized by France in the nineteenth century, but its local Mozabite architecture informed Le Corbusier’s modernist designs. Attia’s structure thus embodies the impact of Algerian culture on that of the country’s former colonizer, a reversal of the expected flow of influence that “repairs” a received idea.

Attia has had solo exhibitions at the at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, United Kingdom (2007–08); Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston (2007–08); Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle (2008); Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris (2012); KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2013); Whitechapel Art Gallery, London (2013); Beirut Art Center (2014); and Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt (2016). His work has also been featured in the group exhibitions Contested Terrains, Tate Modern, London (2011); “Performing Histories (1)”, Museum of Modern Art, New York (2012); “Dix Ans du Projet pour l’Art Contemporain”, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (2012); “After Year Zero”, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin (2013); and “Art Histories”, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg (2014). Works by Attia were included in Documenta, Kassel, Germany (2013), and the Lyon Biennial: “La vie moderne” (2015). A retrospective of his work opened at the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne, Switzerland, in 2015. Attia is the recipient of several awards, including the Marcel Duchamp Prize (2016) and the Joan Miro Prize (2017). Attia lives and works in Algiers, Berlin, and Paris.

-

Abdulnasser Gharem More

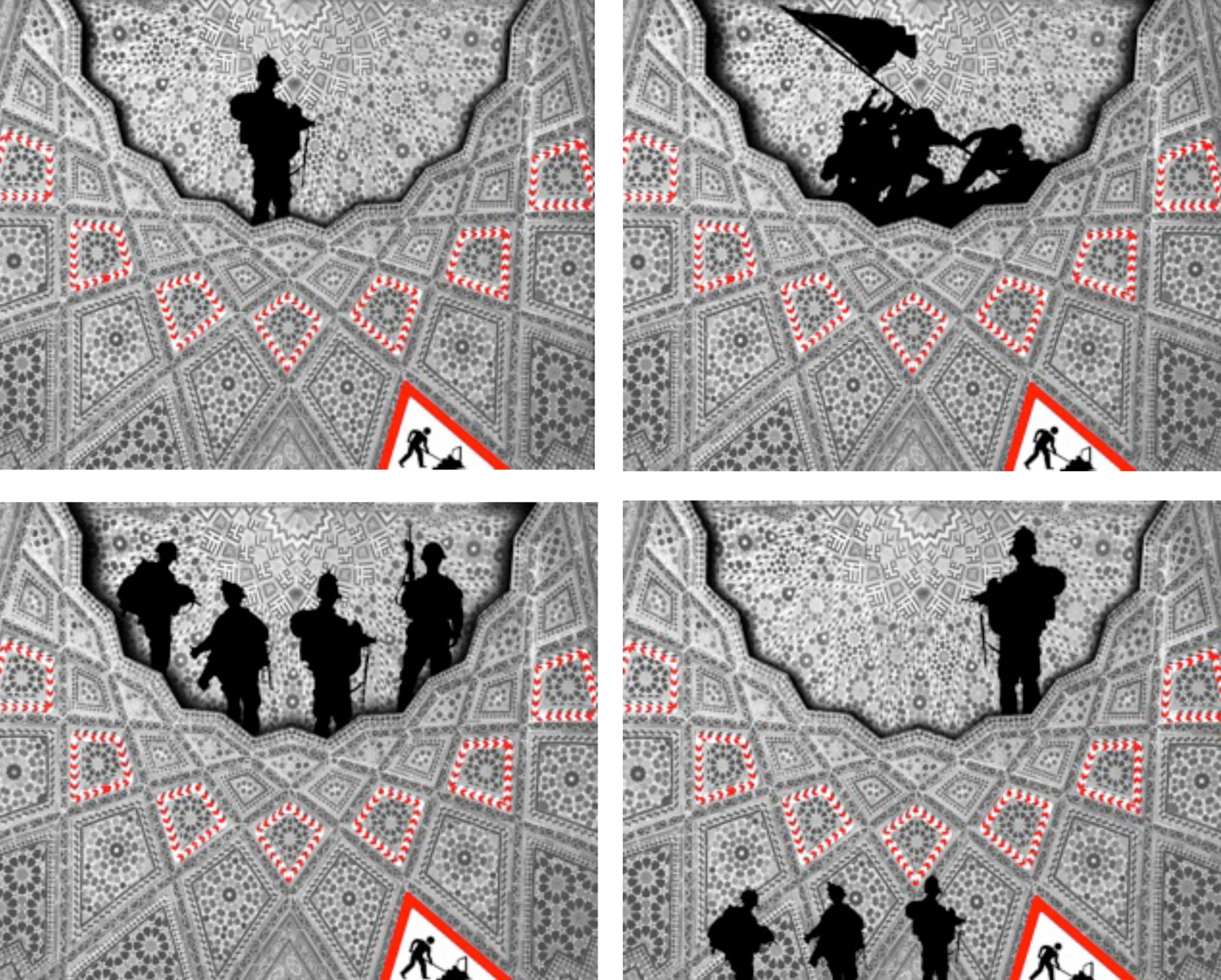

Abdulnasser Gharem, whose artistic works have been shown in Europe, the Gulf states and the USA several times, is known for his use of the stamps of the Austrian company Trodat. Used as medium for his images, the small stamps symbolize bureaucracy, control and authority which he and his contemporaries have to struggle with day in, day out in Saudi Arabia. “The company Trodat produces the objects of authority and bureaucracy

that influence my country. I am now presenting these stamps in my own works, showing them to the public living in the country in which I made them.” The ‘bureaucratic processes’ of progress, which exploded after 9/11 are having a negative impact on our society. I am now trying to use art to defuse these objects and to thus lay claim to a true path of progress. This is my mission,” as Abdulnasser Gharem puts it. Abdulnasser Gharem was born in 1974 in the Saudi Arabic town of Khamis Mushait where he lives and works today. After graduating from the King Abdulaziz Academy in 1992, he then studied at the Leader-Institute in Riad in 1992 and at the renowned Al-Meftaha Arts Village in Abha in 2003. In 2004 Gharem, together with the Al-Meftaha artists, organized a group exhibition with the title „Shattah“, which called into question the existing forms of artistic practice in Saudi Arabia. Since then Gharem has organized exhibitions in Europe, the Gulf States and the USA. His work has also been shown at the Martin-Gropius building in Berlin and at the Biennials in Venice, Sharjah and Berlin. Recently Gharem wrote history when his installation „Message/Messenger“ was sold for a world record price at an auction in Dubai. Abdulnasser Gharem’s works are thus meanwhile among the most expensive ones in the art market of the Gulf region. Gharem donated the proceeds from this sale to “Edge of Arabia” to promote art education in his homeland. His first monograph titled „Abdulnasser Gharem: Art of Survival“ was published in London in October 2011. -

Radhika Khimji More

There are few do-overs in life. Imagine the painting that never quite came together; the magazine article that fell just short; the song whose hook never separated from the bass line –the deadline came round, the document was attached to the email, and off went your work into the world, ready or not.

Who ever gets a second chance?

Radhika Khimji’s second exhibition at Galerie Krinziger follows her 2017 “Becoming”, when she showed photographic collages, small-scale drawings, and large wooden cut-outs suggesting the silhouettes on bodies. As part of Krinziger’s studio program, she made the works in situ, testing. But, she says, she knew that the pieces weren’t ready. Five years later she has returned to the work, slowly and meticulously adding to the same drawings, composites, and cut-outs to make them more dynamic in the gallery space, in the appropriately named “Adjusted Becoming”.

Khimji, who grew up in Oman and lives in London, originally made the works by painting in oil and gesso on wood, collaging together fragments of photographs to suggest scenes midway between a body and a landscape: a kind of Rorschach test of narcissism, playing, she says, on the human tendency towards anthropomorphism, or the way we like to see everything as images of ourselves. In the paper and wood collage “A mountain built rust in the system” (2022), a pointed protrusion jutting upward could be a mountain and two protrusions hanging downwards breasts – how quickly we read these elements. The adjusted artworks retain this oscillation between body and landscape, but have grown in confidence and complexity. She has arranged a number of them in new constellations; to others she has added minute, net-like patterns covering areas of the collages. They highlight elements of the works that can be perceived as bodily, as if they were a strange, scaly or even digital skin: a suggestion of animalistic appearance that accentuates the contiguity between man and landscape.

Khimji has been painting these patterns on her photographic and collaged works since 2001. The practice is inspired by the necklaces that Khimji’s family places on devotional statues of Krishna every morning. By adding to them, Khimji transforms the paintings from representational objects to ones that act performatively: as for the icons, her ritual awakens them.

This idea of activation has become fundamental to her practice, and she sought in other ways to concentrate attention on the performative capability of the artwork. The titles of the works show the bodies arrested mid-gesture – “Right Leg Up, She Is Sitting, I Stepped Over a Hill” – emphasising bodies perpetually in motion. She incorporated a circular structure into the centre of the gallery, hanging the cloth and paper work “The Ring and the Necklace” (2022) inside. The idea was based on paved circles that surround trees in Vienna – an everyday bit of urban design that causes walkers to swerve and weave without even realising it. Here, a stone framework approximating the brickwork keeps the viewers at a distance, positioning the artworks as bodies or structures that must be moved around.

For Khimji, the idea of construction is read as a space of becoming: a site where one’s inner world can be built up alongside the structures of an outer world. In Oman, where construction was rampant throughout Khimji’s childhood in the modernising nation, she learned to see construction as a mode of potential: to see the walls, ceilings, courtyards that would eventually be, but not yet.

For “Adjusted Becoming,” Khimji works to seize that “not yet” moment of the awakened space between the picture plane and the viewer. A visitor walking into a room, she has said, is like turning the lights on. With the works stacked up against each other, leaning against each other, hanging from the ceiling, the space of viewership becomes the central focus of the viewer’s experience – not the doll-like, ritual objects, but the act of viewing, looking, and thinking about them. (Melissa Gronlund)

Radhika Khimji was born 1979 in Oman and lives and works in Muscat and London. From 1998-2002 she studied at the Slade School of Fine Art and from 2002-2005 at the Royal Academy of Art where she completed her studies with a Fine Art Post Graduate Diploma. In 2007 she graduated at the UCL with a Masters Degree in Art History. After her Residency and a solo exhibtion at Krinzinger Schottenfeld in 2017 and 2018 Radhika Khimjis works were shown at a solo exhibition at Galerie Krinzinger in 2019. She has had solo and group exhibtions at the Experimenter, Kolkata, India 2021, Drawing Biennal, Drawing Room, London 2019, 2017,UAE Marrakech Biennale 6, Marrakech, 2016 Gallery Sarah, Muscat 2016, 4thGhetto Biennale, Port Au Prince, Haiti 2015, Gallery 88, Kolkata, India 2015, Katara art center, Doha, Qatar 2012, Barka Castle, Barka Sultanate of Oman 2010 and Saatchi Gallery, London, 2010.

From June 21 – August 21, 2022 her works were shown at Summer Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts, London. Rahdhika Khimji was one of five artists exhibiting at the first Omani Pavillion at the 59th Venice Biennial until November 27, 2022. -

Maha Malluh More

In “Food for Thought“ I constructed a tower using enameled dishes and bowls, which were once used for serving food in Saudi Arabia. When an object no longer serves its original purpose, it can get a new lease on life, through adaptive reuse by serving an entirely new purpose, thus preserving the heritage of its significance. (Maha Malluh)

The Shemagh Mirage collection concentrates on the theme of the urban man in Saudi Arabia. In unravelling this complex social reality, the works address the discourse of patriarchal values in Saudi Arabia. This cannot be done without being seen in the light of globalisation and the changing world order. In doing so, the series hopes to take part in the dialogue of clarifying misconceptions of gender roles and expectations.

In addition to the exploration of gender discourses, the whole fabric of material culture is studied. The series presents a range of objects more global in resonance in contrast to the material culture of the traditional Saudi Arabian headgear. The objects have no cultural specificity, which point to the submission of Saudi society to global pressures and markets. Shemagh Mirage responds to Saudi experiences of rapid urbanization.

The work draws us into the transformation of society from one which takes part solely in the Arabo-Islamic culture to one which is also active in global trade and commerce. As seen from the overlapping images used in each photogram, this tension shows us the complexities of the very fabric of modern Saudi man and society.

Maha Malluh, “Tradition&Modernity”

“Tradition and Modernity” is a series ultimately about society’s transformation from tradition to our present modern day. The artist has found photograms most appealing; toying with objects and experimenting with different arrangements has become a playful expression of collective and personal experiences.

Occasionally understood as a force of ‘retention’, tradition can cause some to feel the need to isolate themselves from modernity’s monstrous reach. Opening the gateway to Paris, modernity and its accompanying high-speed aircraft, finds people screened, probed into and investigated. There means that there is no room for privacy and retention as all is exposed.

The objects chosen in these photogramic collages include trinkets relating to the country’s cultural heritage and present experience of modernity, part of Saudi Arabia’s material cultural make-up. Considering this multilayered history of past and present, the photograms can be posited in a discursive practice which attempts to deconstruct modernity’s obscene obsession with material culture.

“Tradition and Modernity”, with its creative employment of photograms is a nostalgic expression for aesthetic appreciation of the everyday, the simple, the humble. -

Ramin Haerizadeh & Rokni Haerizadeh & Hesam Rahmanian More

Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian's early collaborative practice formed as early as 1999 in Tehran, though the artists reside in the U.A.E since 2009 in exile. The trio have practiced a model of how to collaborate, creating a self-sustaining creative life; how to build an aesthetic and undermine it; how to be politically acute and humorous, generous and eccentric. Their home is a working studio which is also a film set and movie theatre, a museum and research center. It is a test site-cum-monastery, an academy-cum-pleasure dome. The house informs their art as it results from both collective and individual endeavor. Yet, they are not a distinct group or collective, there is no name or label for the trio as their practice often evolves around other artists and friends, which translates into multiple forms. Ramin, Rokni and Hesam’s work is often referred to as a landscape where the complex nature of processing is integrated in the nested system that forms the landscape of their shows. In their art making, production is performance and the performance is a collective action leading to dance, art, and politics.

-

Alfred Tarazi More

1980, born in Beirut (Lebanon). Lives and works in Beirut (Lebanon). In an artistic practice shaped by the ultimate event horizon of the Lebanese Civil War, Alfred Tarazi deploys his visual strategies in order to dig out fields of memory, emplaced haphazardly in a vast expanse of the present tense, often without direction or destination. A narrative emphasis occurs, at the root of which the artist is unearthing critical and historical tools to read past events provided by the past itself in the manner of a reluctant heritage. Tackling the Lebanese obsession with history, Tarazi playfully interrogates its questionable sources and selective archival practices, highlighting the role of the past as both origin and destination. With merciless realism intersecting both fiction and historiography, the artist articulates the spectacle of war as a syntax of the unimaginable, broken down piecemeal to a lived present. This archaeology of the now-time does not aim to restore, but rather to represent a historical condition through fragments of anomalies and singularities. The field of representation, however, prevents distance and enclosure: it is a laboratory, a journal, a political inquiry, a memory site and a reality marker.

Alfred Tarazi is a multi-disciplinary artist based in Beirut. In 2004, he graduated with a degree in Graphic Design from the American University of Beirut. His entire body of work, ranging from painting, photography, drawing, digital collage, sculpture to installation, revolves around complex historical investigations. His work has been acquired by prestigious public and private collections, including the British Museum and the Museum of Modern Art.

-

Ahmed Mater More

Ahmed Mater (born 1979 in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia), and grew up in Abha. An artist and physician who studied at King Khalid University, Abha, Mater uses photography, film, video, text, and performance to entwine expressive and politically engaged artistic aims with the scientific objectives of his medical training, blending conceptual art tactics with an investigation of traditional Islamic aesthetics. His recent practice constitutes an unofficial history of Saudi sociopolitical life within a global context.

Early works such as “Magnetism” (2009), a photograph of a black magnet surrounded by iron filings that suggests the congregation of pilgrims around the Ka’aba, fuse Mater’s scientific and religious interests. He continues to explore the connections and contradictions between the two fields in his series “Illuminations” (2008–10), in which x-rays are juxtaposed with Islamic inscriptions and gold-leaf decorations. It is, however, through his series “Desert of Pharan” (2012), that he most poignantly exposes the paradoxical aspect of the intersection of Islamic culture and globalization. Mater began this ongoing photographic sequence in order to document the explosive real-estate development in Makkah, where the old city is rapidly being replaced by luxury hotels and greatly expanded mosques. Taking his title from the Old Testament (Pharan was the ancient name for the area around Makkah), Mater’s series represents the clashes between politics and religion, old and new, which define the holy city today. The powerful work “Disarm 1–10” (2013), one part of “Desert of Pharan”, consists of ten light boxes with photographs taken from a helicopter. The images of the helicopter’s display screen, which show a mountainous terrain punctuated by the Makkah Royal Hotel Clock Tower—the world’s second tallest building—are tinged with the blue shades of surveillance footage, imparting an ominous tone to a city in the process of hyper-commercialization.

“A boy stands on the flat, dusty rooftop of his family’s traditional house in the south-west corner of Saudi Arabia. With all his reach he lifts a battered TV antenna up to the evening sky. He moves it slowly across the mountainous horizon, in search of a signal from beyond the nearby border with Yemen, or across the Red Sea towards Sudan. He is searching, like so many of his generation in Saudi, for ideas, for music, for poetry – for a glimpse of a different kind of life. His father and brothers shout up from the majlis (sitting room) below, as music fills the house and dancing figures appear on a TV screen, filling the evening air with voices from another world. The boy with the antenna is a young explorer in search of contact with the outside world, reaching out to communicate across the borders that surround him. The boy will become an artist, with the same spirit of creative exploration and curiosity.“ (Antenna Series).Mater has had solo exhibitions at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia (2004); Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, London (2006); Artspace, Dubai (2009); the Vinyl Factory Gallery, London (2010); Sharjah Art Museum (2013); and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. (2016). His work has been included in group exhibitions at the British Museum, London (2006 and 2012); Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2011); Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris (2012); Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Museum of Islamic Art (MIA), Al Cornische, Doha; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City; and Ashkal Alwan in Beirut, Lebanon (all 2013); and Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, and New Museum, New York (both 2014). He participated in the Sharjah Biennial (2007 and 2013); Cairo Biennial (2008); and Venice Biennale (2009 and 2011). Mater lives and works in Abha and Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Exhibition text

More

Krinzinger Schottenfeld decided to develop an exhibition for the annual curated by festival, which underlines a deep research on the artists and their practice in the Middle East. This is justified by the 15-year-long strong presence of the Galerie Krinzinger not only in the yearly Art Dubai Fair, but also by the gallery's continuous visits of the MENA-Region and contact with the local artists, who then successfully joined the gallery program. Gallery Krinzinger invited curator Verena Formanek, as she has knowledge and expertise in these regards and has an extensive experience in working in Abu Dhabi and the rest of the Middle East.

This exhibition presents artists from the Arabian Peninsula whose work focuses on the topic of orientation, camouflage, and identity. The objectives of mounting this exhibition in the Gallery Krinzinger Schottenfeld, Vienna, are two-fold: showcasing the context of what constitutes contemporary art history in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as well as for the United Arab Emirates, Reem Fadda mentioned once:” …to establish a framework for understanding the links between the artistic practices of the past generations of contemporary artists in the United Arab Emirates and balance them with the current artistic themes relevant for the Gulf region.”

Secondly, discussing first the exhibition concept regarding the impulse essay “The Neutral” with a curator, born in the Emirates and living between two worlds (as most of her generation in the gulf), France and the United Arab Emirates: Alia Zaal. She connects her work with the tradition in the UAE, represented by her father, an artist, and explains: “My work has been inspired by my father’s weak eyesight as a result of which he was forced to approach art differently, paying a lot of attention to detail”. During her residency in France she responded to Impressionism, studying the natural landscapes of Vétheuil, Abu Dhabi and Dubai, both in their natural and artificial ecosystems, finding connections between her own UAE landscape and the impressionist one.

We decided to showcase the following artists with artworks encompassing the reflection about how to find your way, your directions in a theme of Neutrality. The theme “The Neutral” raises questions regarding passivity vs. activity and how you should find your way in this complexity of questions? Therefore, the artists in this exhibition are searching for their ways.

For continuing and finding his way the artist Mohamed Kazem is represented with his exceptional artwork “Direction (Steps), 2011-2013” and in “Photographs with a Flag, 1997”, which documents his famous performance. In “Collecting Light, 2021” not only the visual appearance is to be seen in his scratching papers but also the sound of the scissors is sculpted on the surface of the paper. While creating the scratches in/on the white paper surface, the artwork can be seen as a two-dimensional work: sculpture, drawing and sound.

Interdisciplinary Emirati artist Layla Juma utilises geometric shapes, in this case circular and elliptical designs, to convey ideas of form and sequence in striking, rhythmic works of art. Her repetitive use of circles and lines evokes abstract contemporary images of (social) codes representing different aspects within a society.

Themes that are raised in Juma’s work are reminiscent of the artist Hassan Sharif’s (+2016) interest in combining drawing, performance, movement and construction in his work, as well as Kazem’s examination of natural processes and social identity. She scrutinises everyday lines and shapes, often dissecting them into pieces and re-assembling them.

The collective work of this generation, which is more or less the age of the UAE itself, gives the place depth and imagination, and more trenchantly, a past and a future, both of which are usually absent from the standard-issue stories on art in the Gulf. Nothing exemplifies this better than the work of Lamya Gargash: her “Presence” series, which was exhibited a year ago in the labyrinthine Bastakiya district, is a catalogue of derelict domestic spaces in Sharjah, Dubai and Ajman, each image capturing a room either abandoned or soon to be so. Lamya Gargash searches for the traces of her history, her parents’ life, and former culture of her country.