VIN VIN Gallery curated by Lucrezia Calabrò Visconti

„Motherless Daughters“

www.vinvin.eu

Curator(s):

Artist(s):

- Pauline Curnier Jardin

- Harun Farocki

- Beatrice Gibson

- Giulia Crispiani

- Delphine Seyrig

- Maria Iorio/Raphaël Cuomo

Exhibition text

More

When Francis Picabia described the machine as a 'daughter born without a mother' he was hoping to propose an original variation on the modernist theme of the correspondence between humans and machines. However, his instinctive superimposition of the technological device on the female body betrayed the generalised fear towards the rising of technological innovation on one hand, and that of sexual freedom on the other – a cross-attack perpetrated against traditional visions of masculinity in the ‘20s. The ‘motherless daughter’ was a symbol of the widespread alarm for the replacement of men by technology, personified in the figure of the wicked woman, insubordinate and lascivious, who was challenging gender norms and therefore the status quo.

The exhibition Motherless Daughters appropriates this injurious definition to claim new stories for it. Using ‘the neutral’ as a key to open a third way between known categories, the project turns the contradictory nature of the term into a burning space for the negotiation of new meanings. The machine born without a mother will be the cinema, as in the technologies and politics embedded in the filmic device. The status of motherless daughters will be a deliberate choice and not a given: losing the mother while demanding the condition of daughters will allow us to challenge the authority of bloodlines, while plotting together forthcoming genealogies. Turning the gallery space into a para-cinematic installation, Motherless Daughters brings together artists who exercise the political potential of film to forge relationships across vast distances and temporalities. Rising voices from the past, and collecting prayers for the future, the works on view shake our understanding of alliance, friendship, and death, invoking a coven of transhistorical sisterhoods.

The screening programme begins with Undead Voices (2019-21) by Maria Iorio and Raphaël Cuomo, that takes its stances from the amateur militant film Donne Emergete!, shot in 1975 by Isabella Bruno. Being ‘damaged beyond repair’ according to archival standards, the film was lost, together with the memory of the contestation movements it documented. Undead Voices incorporates the original movie by Bruno, reanimating the voices of the feminist communities it portrayed. Past and present feminist practices resonate together in the ghostly sequences we see, hidden in the interstices between what is considered a film and what is not, claiming a space between what is alive and what is dead.

I hope I'm Loud when I'm Dead (2018) was developed by Beatrice Gibson together with poets CAConrad and Eileen Myles. Their warm voices guide us through a narration that intertwines footage of global politics in times of civil unrest with private images from the author’s family life. Poems and reflections constellate the film, where “I hope I’m loud when I’m dead” feels as much a wish as a threat; a firm invocation of strength when grief, destruction, and fear seem impossible to bear. Crossing through chaos with empathy and sharpness, the film reveals itself as a promise for the future and a testimony for a daughter: “I wanted to put all these voices in a frame for you, so that one day, if needed, you could use them to unwrite whatever you are told you are supposed to be”.

Pauline Curnier Jardin’s Qu’un sang impur (2019) re-stages the film Un chant d’amour (1950) by Jean Genet, replacing the original homoerotic love story between two inmates in a prison with an untamed celebration of the erotic power of post-menopausal women. Questioning traditional representations of elderness, the group of women is dangerous and fierce, strong in their resolution to live in a way that was not calculated nor approved by society. Jubilantly uncanny, the gang is composed of killers and outlaws, who escaped the imposition of being objects of desire and can therefore freely feast on their ‘impure blood’.

The three movies are interspaced by Harun Farocki’s short films Bedtime stories. Commissioned in 1976-77 by a German TV channel for kids, the video series features Farocki’s daughters as actresses. The two girls describe to each other huge infrastructures and devices such as railways, ships and bridges as if they were majestic, almost magical machines. Following their dreamlike game, footage of these objects appear on the screen, while they fall asleep together in their twin bed.

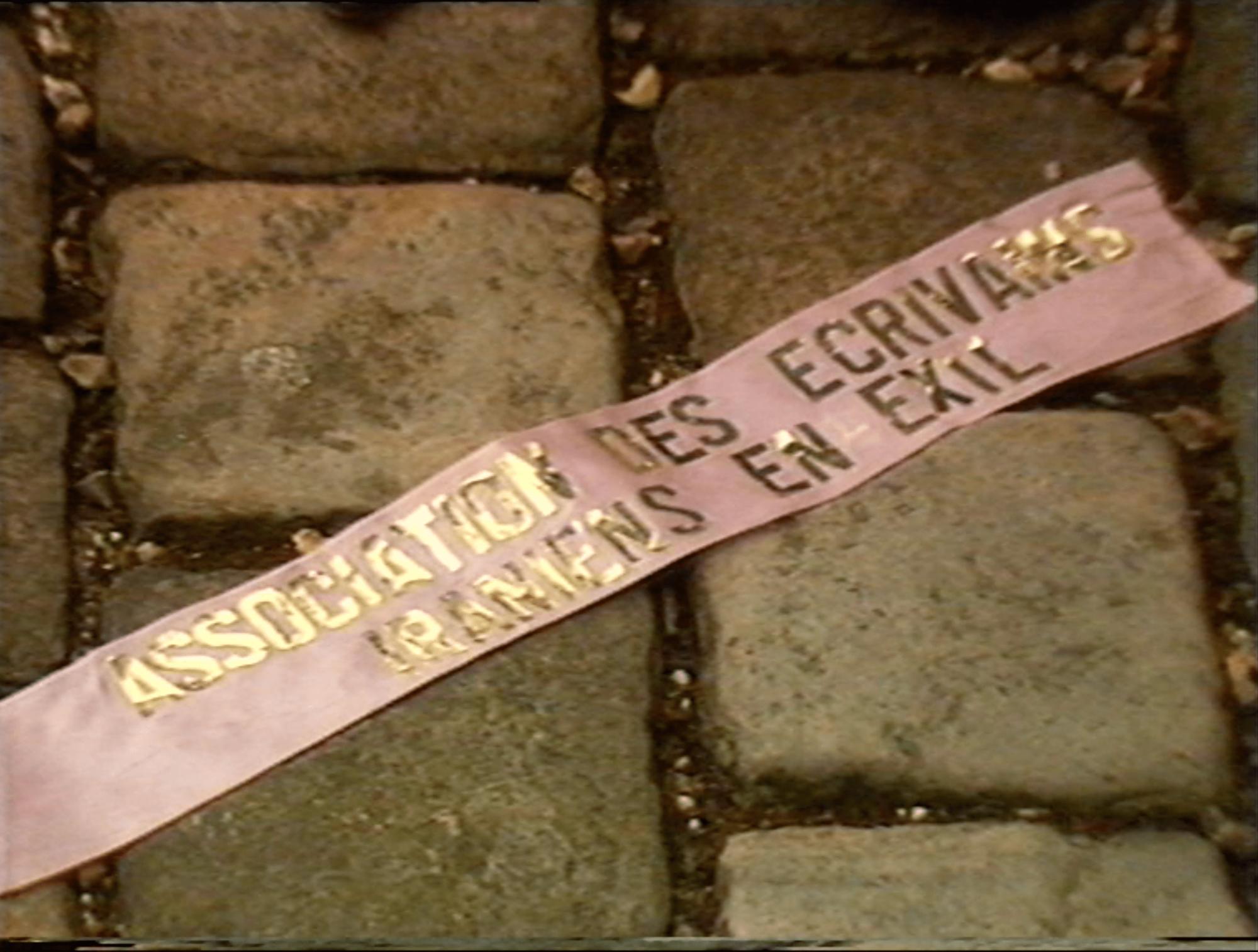

Outside the cinema, the exhibition space is transformed into an urban-looking landscape, inhabited by a street lamp, a barricade, and a waste bin. Evoking the streets of Paris, the room acts as an intermezzo between the Wien street outside the gallery and the dark room of the cinema. The sculptures are part of Peaux de dame by Curnier Jardin, a series of artificial leathers shaped as carnal envelopes of crushed women. The bizarre objects are skin-like leftovers of bodies emptied out of their contents, that now fill the street with their ghostly presence. Nearby, a TV monitor screens images from the Montparnasse cemetery, revealing a tombstone covered in wreaths of flowers, ribbons and letters. It is Simone De Beauvoire’s grave, as Delphine Seyrig recounts it in her film Pour Mémoire (1987), which documents the first anniversary of the philosopher’s death. The camera closely follows the garlands of flowers, while voice-overs read the countless messages that were left on the gravestone to remember her legacy.

Pour Mémoire introduces us to the condition of mourning, a hybrid space confusing the boundaries between life and death. As Barthes declared when he first started drafting his lessons on ‘the neutral’ in 1977, “to get myself vividly interested in what is contemporaneous to me, I might need the detour through death”. He was referring to the so-called “library of dead authors'' he was reading, but also to the grieving of his own mother, who had just passed away. “To mourn is to be alive” he wrote, while dividing his time between the lessons and his Journal de deuil, a mourning diary where he grappled with his loss. Motherless Daughters embraces Barthes’ desire to “make the dead think in oneself”, mourning being a time to evoke those who are not alive anymore, making their voices heard again through our throats.

Before leaving the gallery, the last work of the show consists of a series of holy cards by artist and writer Giulia Crispiani. Bearing prayers, lamentations, or chants, the texts summon past and future generations of motherless daughters. Just as the professional mourners, recruited to cry louder at other people’s funerals, Crispiani’s poems invoke, embody and magnify our voices, disseminating them outside the building, calling out for sisterhoods that have yet to be.