Crone Wien curated by María Inés Plaza Lazo

„Crime as Ornament“

www.galeriecrone.com

Curator(s):

Artist(s):

-

Havîn Al-Sîndy MoreBorn in the Kurdish autonomous region of Iraq, the artist Havîn Al-Sîndy works in Berlin, Düsseldorf and Kurdistan. Al-Sîndy studied at the State Academy of Fine Arts Stuttgart and the Düsseldorf Art Academy, where she completed her studies in 2018. At the same time, she studied biology and chemistry at the University of Duisburg-Essen. In 2021 she received the scholarship of the Baden-Württemberg Art Foundation. In 2022 Al-Sîndy was awarded the Egmont Schaefer Award for Drawing and in 2023 the Helmut Kraft Foundation Award for the Promotion of the Visual Arts. She currently teaches at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Braunschweig. Havîn Al-Sîndy's works can be found in the fields of sculpture, painting and moving images. She deals with artistic and scientific processes of visualisation, finds languages for the difficult to say and the ambivalences in the production of visibility itself. Her working method is processual and mostly collaborative. Again and again, the focus is on a dialogue across generations - an interest in and engagement with one another.

-

Shilpa Gupta MoreShilpa Gupta (born 1976 in Mumbai, India) lives and works in Mumbai. Gupta's artistic practice encompasses a wide range of media, including manipulated found objects, video art, interactive computer-based installations and performances. Her artistic interests revolve around the perception and transmission of information in human life. In her work, she investigates how objects, places, people and experiences are defined. In doing so, she explores the various dynamics that shape these definitions – for example borders, labels, censorship and security. Gupta has had solo exhibitions at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, the Arnolfini in Bristol, the OK in Linz, the Museum voor Moderne Kunst in Arnhem, the Voorlinden Museum and Gardens in Wassenaar, the Kiosk in Ghent, the Bielefelder Kunstverein, La Synagogue de Delme Contemporary Art Centre and the Lalit Kala Akademi in New Delhi. Her works have been shown at the Venice Biennale 2019, the Berlin Biennale 2014, the Sharjah Biennale 2013, the New Museum Triennale 2009, the Yokohama Triennale 2008, the Lyon Biennale 2009 and the Liverpool Biennial 2006, among others. In 2015, she took part in the joint Indian-Pakistani exhibition My East is Your West, which was organised by the Gujral Foundation in Venice.

-

Ayham Majid Agha MoreThe actor Ayham Majid Agha was born in Syria in 1980 and lives in Berlin. From 2005 to 2012, he was a member of a theatre studio that performed interactive theatre projects in Syrian villages. Between 2006 and 2012, he taught at the renowned Damascus University of Performing Arts, after which he worked at various theatres in Damascus, Manchester, Amman, Beirut, Cairo, Seoul and Hanover. Until the end of the 2017/2018 season, Majid Agha could be seen as an actor at the Maxim Gorki Theatre in Berlin in Sebastian Nübling's production of In Our Name, Heiner Müller's Der Auftrag and The Situation by Yael Ronen & Ensemble. The Situation was invited to the 2016 Theatertreffen and was voted “Play of the Year 2016” by “Theater heute”. Together with the writer Olga Grjasnowa, he created the multi-part interactive cookery show Conflict Food. Since 2016, he has directed the Exil Ensemble at the Maxim Gorki Theatre, where he also staged his play Skeleton of an Elephant in the Desert.

-

Marcel Odenbach MoreMarcel Odenbach (born 1953 in Cologne, Germany) is a pioneer of video art and still one of its most important representatives today. He originally studied architecture and art history and researched collective mechanisms of repression. In his videos and collages, Odenbach refers to the crimes of National Socialism, the means of power of the GDR regime and the atrocities committed by Europeans in their former Afrian colonies as a reaction to what has long been unspoken. Odenbach lives and works in Cologne, Italy and Ghana. He uses similar approaches for his collages and videos. For both, he draws on images, texts, and illustrations from newspapers and magazines. His large-format collages initially show clearly recognisable motifs on a macro level, but on closer inspection turn out to be compositions of hundreds of individual images. In 2021, Marcel Odenbach received the Wolfgang Hahn Award by the Gesellschaft für Moderne Kunst at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne. His works were shown at documenta 8 in Kassel in 1987. Odenbach's solo exhibitions took place at the Kurt Tucholsky Literature Museum, Rheinsberg, the MAIIAM- Contemporary Art Museum, Chiang Mai, the Museum Folkwang, Essen, the Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, the Stichtig De Appel, Amsterdam, the Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, the Museum Ludwig, Cologne, the Kunsthalle Wien, the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai among others.

-

Noara Quintana MoreThe artist Noara Quintana (born 1986 in Florianópolis, Brazil) lives between São Paulo, Brazil and Los Angeles, USA. Her practice centers on the materiality of everyday objects and their relations as an index of the histories of the Global South. Through installation and sculpture, Quintana's work points to traces of exchange, forms of architecture, and an ongoing reimagination that contests the legacy of the colonial imaginary. She sees traces of people, practices, and identities in the materials and forms of everyday objects, and she foregrounds the submerged gestures of a Global South shaped by the colonial process. Quintana holds an MA in Visual Arts from São Paulo State University. Recent exhibitions include Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Museu de Arte de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Pivô + KADIST, São Paulo, Frestas Triennial, Sorocaba, and SAVVY Contemporary, Berlin. Noara was a recent artist-in-residence at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris, Pivô Art and Research, São Paulo, and a 2020 Institut Français Lauréate of the Cité Internationale des Arts.

-

Pauł Sochacki MorePauł Sochacki (born 1983 in Krakow, Poland) lives and works in Berlin. At first glance, his painting moves between abstraction and romanticism. Familiar motifs seduce with poetry and humour to complex readings in which mythical creatures and quotations from the world of art meet casually. Although his pictures sometimes appear childlike and fairytale-like, they often represent a sharp reflection of social conditions, which also occupy Sochacki as co-editor of the street magazine Arts of the Working Class. The artist scrutinises social and cultural value systems as well as political and economic ones. He subtly comments on them through the seemingly innocent motifs of his paintings.

-

Kandis Williams MoreKandis Williams (born 1985 in Baltimore, USA) is an artist, author, editor and publisher based in Berlin and Los Angeles. Her collages, performances and publications have received worldwide recognition. Williams' works often deal with contemporary critical theories, primarily on racism, nationalism, authority and eroticism. In many of these themes, she draws on her experiences growing up in Baltimore and as a teacher, which she combines with historical references. She collages images from magazines and archival material to create highly structured visual dialogues. Kandis Williams' work has been shown at MoMA, New York, the Brooklyn Museum, the Joan Miro Foundation, Barcelona, the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, the VCU Institute for Contemporary Art, Richmond, the 2015 Venice Biennale and the 2022 Whitney Biennial. A solo exhibition will follow in 2025 at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. In 2023 Kandis Williams received the FOCA Fellowship Los Angeles, in 2021 she was the winner of the Mohn Award of the Foundation for Contemporary Arts, New York.

-

Philip Wiegard MoreThe artist Philip Wiegard (born 1977 in Schwetzingen, Germany) lives in Berlin and works mainly in the media of sculpture and photography. He has been working with colored paper for several years. Having visited numerous collections of colored paper throughout Germany, he is particularly interested in Herrnhut paste paper and its historical production and distribution conditions. In his practical work, he attempts to reproduce historical patterns, focussing on the performative aspects of the creation process. Since 2013, Wiegard has been realising the ongoing performance project Kids’ Factory, in which children produce hand-patterned wallpaper using the paste paper technique for a fee. His abstract designs thus emerge from an ‘ethic of cooperation’ (Wolfgang Ullrich).

Exhibition text

More

The exhibition refers to the essay Ornament and Crime by the Austrian architect and publicist Adolf Loos from 1908, which is considered a key impulse for the dawn of modernism. In this essay, Loos establishes his vision of reduced, unadorned form. He castigated ornamentation as an intolerable, degenerative phenomenon of the aristocracy and the upper bourgeoisie, which, like its creators, had outlived its usefulness and had to be replaced by sober, objective honesty. At the same time, he distinguishes the ornaments of “simple cultures”, which today would be categorised as belonging to the “global South”, from the exuberant, ornamental dictates of taste of the European elites, and he recognises their truthfulness and beauty.

In the exhibition Crime as Ornament, curator María Inés Plaza Lazo poses the question of the extent to which Loos' postulate was the arrogant expression of a Western cultural hegemony that marginalised foreign aesthetics and formal language - or, on the contrary, called for the differentiation that makes sincere respect and undivided recognition of the “other” possible in the first place. In this respect, she takes up the ideas in this year's Curated by impulse text by Noit Banai, which deals with cultural diversity and the subjective perception of beauty and could be understood as a counter-thesis to Loos' rigid, strict idea of aesthetics.

The works on display reveal precisely what Banai refers to and what Loos already hinted at: the complexity of the debates we are having today about identity, repression and paternalism. The deep roots of these debates in the distant past. And the difficult-to-resolve contradiction that arises not only from different cultural influences, but also from perspectives, perceptions, categorisations, interpretations - and misunderstandings.

Curator's essay

The complexity of human experience becomes even more elusive the more we try to describe it in words. After the two world wars, the simplification of universalist imperatives was enforced. This urge to eliminate parallels, ambiguities, and contradictions affected the collection, the establishment of archives, and the design of buildings like the one hosting this exhibition: all were intended to maintain a chronological sorting of the world, a technocratic, imperial order that simultaneously celebrates and conceals power structures.

However, exhibition spaces also serve silence and the narration of the unsaid. I want to add both to the antitheses of Loos’ ideas in his controversial essay, "Ornament and Crime," which advocated clearer, simpler, and more unified narratives at the beginning of the 20th century. Loos’ call for reduction and clarity is trapped in an old nervous system, in forms of belonging and recognition conceived and enforced only for a certain type of citizen. These forms are currently undergoing violent change, in the chaos of alternative, communal attempts at societal formation. We have had the opportunity to understand and multiply history and the present through non-binary, interspecies, and post-colonial perspectives.

Constantly, images of amputated children appear on the glass surfaces of mobile devices. The structure between dying in a distant place, a technocratic system orchestrating streams of images of this dying, and a moral economy where these images serve as tokens is convoluted, disturbing, and monstrous. There is a crack in the so-called civilization, following an epistemic landslide whose consequences seem neither foreseeable nor navigable. Helplessly, we witness daily how crimes become ornaments on our screens.

Loos’ rejection of ornaments ultimately expresses a Western cultural hegemony that marginalizes other aesthetic traditions and forms of expression. This may have been relativized today. Yet, the recognition of those ‘other’ forms of expression only occurs either in resistance or through exoticization, which still maintains the hegemonic order. Vienna today offers a diverse architectural mix of historical buildings, modern architecture, and contemporary design. This allows us to vividly trace both continuities and breaks in thought and practice in architecture, design, and artistic production.

The text by Noit Banai for Curated By 2024 deserves not only to determine the intellectual framework of this festival but also to stand directly in conversation with artworks. Banai’s plea for a diverse and inclusive approach to design and historiography should be seen in opposition to Loos’ rigid ideas. By focusing on cultural diversity and the subjective perception of beauty and aesthetics, Banai’s arguments directly counter Loos’ theories on ornaments. Subjective aesthetics are not only what interests me personally as a curator; they also do not shape the artworks gathered in the Galerie Crone. Rather, these works show forms of contemplation of subjectivities only insofar as they differentiate between personal preferences, cultural belonging, and historical contextualizations.

In "Belle Epoque dos Tropicos," Noara Quintana seeks lost symbols of European colonization in Brazil. The rubber cultivation and the region’s economic crisis affect not only her entire family but also shape her artistic work. This is based on the materiality of everyday objects, in which ghostly traces of colonial imagination like Art Nouveau fantasies recur, as well as those of individuals, practices, and identities silenced by the neocolonial structures of modernity. Quintana’s ornaments on fluorescent rubber intertwine the exoticized and extinct, the recognized and repressed.

Philip Wiegard’s wallpapers serve as a kind of preamble to the exhibition: his abstract designs emerge from an ethic of cooperation, as Wolfgang Ullrich beautifully describes in Wiegard’s catalog for his solo exhibition at Schloss Gandegg. patterns consist of disparate colors, shapes, and textures. They are always collectively painted by children in carefully prepared workshops. Wiegard remains the initiator of the process, paying each child for their participation. Loos saw ornamentation as a cultural "regression" (to where, exactly?) and considered simple, unadorned forms as expressions of moral and intellectual integrity. For Wiegard, the ornament represents a universal openness to the diversity of human experience and the richness of possible perspectives.

Paul Sochacki’s paintings allow mythical creatures and quotes from the art world to meet casually. His paintings move, at first glance, between abstraction and romanticism. Familiar motifs entice poetry and humor into complex interpretations. As we delve into his stories, we begin to recognize connections to real situations and their social contexts. Although Sochacki’s images sometimes appear childish and fairy-tale-like, they often present a sharp reflection on social conditions. This also concerns Sochacki as my co-editor of the street magazine Arts of the Working Class. In this exhibition, he will link the various spaces into a network of speculation about the values of art.

Loos’ term "tasteful forger," which he used to describe artists creating ornaments in his time, brings me to the work of Marcel Odenbach. Since the 1970s, Odenbach has developed a specific visual language using archival material, film and television cuts, and self-produced images and film sequences, experimenting with film, rhythm, sound, and sampling. In his series "Außer Rand und Band," created for the Hamburg association Griffelkunst, he arranges motifs from various sources associatively or thematically. Some cutouts originate from the storming of the Capitol by Trump supporters in Washington in 2021. Others show a grim chapter of German colonial history in Africa. By adopting the form of historical wallpaper patterns, which do not follow notions of beauty or decoration but illustrate and thereby critique, Odenbach contrasts with Loos and aligns with Siegfried Kracauer’s essay "Ornament of the Masses," which analyzed film and photography as expressions of the new aesthetics of mass culture.

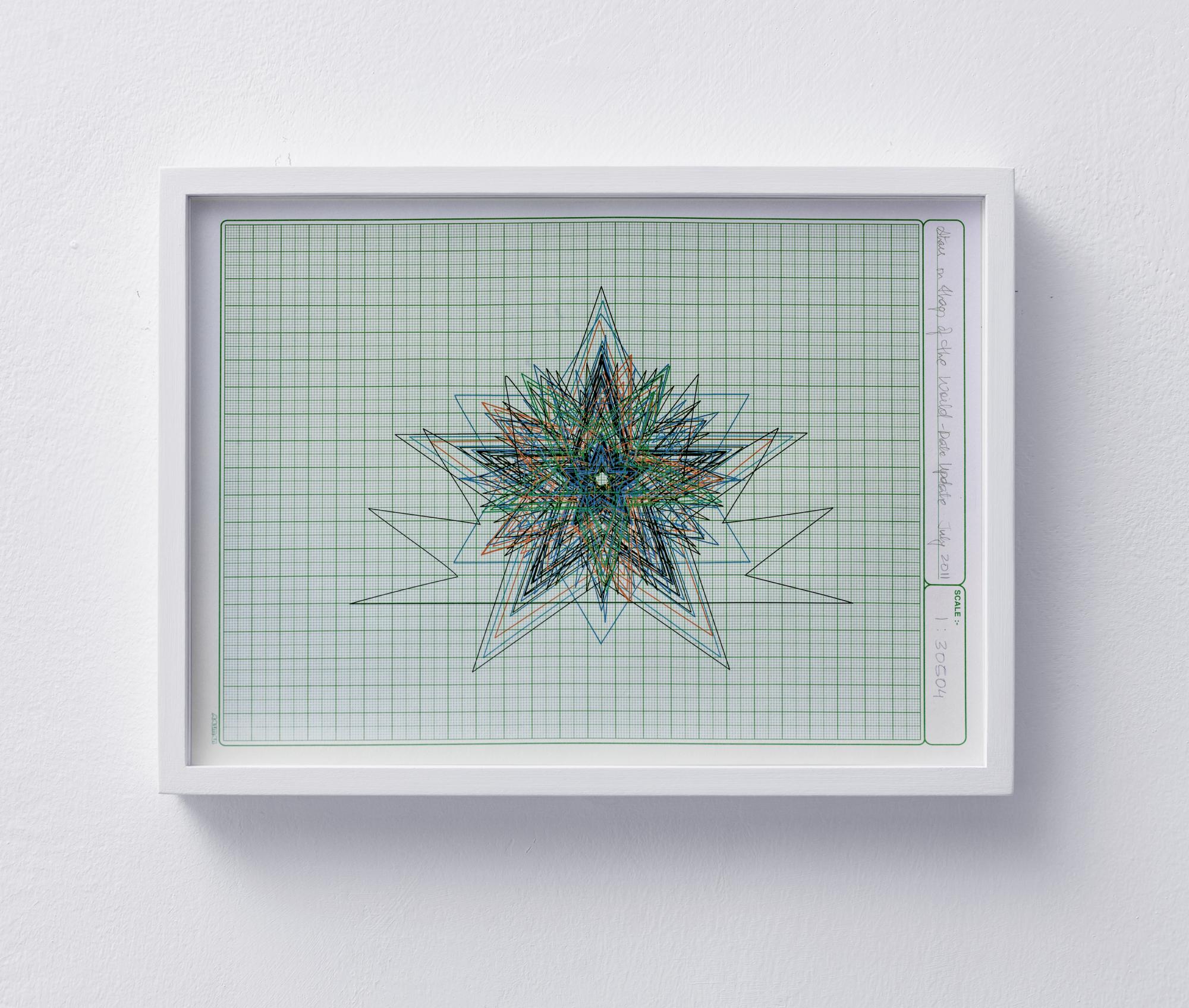

There are decorations and ornaments that do not become outdated through enforced modernization but through their use. Shilpa Gupta’s installation "Stars on Flags of the World" arose from the artist’s ongoing interest in the impermanence of geographical markers and imagined communities, nationality, and mobility. "How is it that all countries tell their citizens they are the best?" Shilpa Gupta asks, quoting a line from Benedict Anderson’s book "Imagined Communities." A heap of stars laid out on the floor invites questioning how competing nationalities can even share the same space or enter into dialogue. Everyone can take the stars home. Thus, Gupta offers an inclusive approach to the question of belonging and manipulates power relations.

The ruins of modernization referenced in the footage and music directly reflect the false promises of modern progress that not only define the architecture and image of cities like Vienna but also the ruins of wars and colonies, which continue to carve deeper divides in our globalized society. Kandis Williams turns the relationship between word and image into sculpture, centering themes like racism, social justice, and moral integrity. The significance of empathy in a society marked by prejudice and ignorance is emphasized in her "Readers" and her collages, which showcase the persistent social inequality between white and racialized people in the USA. These images of normalized violence and the criminalization of Black bodies are as old as Harper Lee’s "To Kill a Mockingbird" (1960), where the protagonists, Atticus and Scout, talk about it being a sin to kill a mockingbird because they just sing their song and harm no one. The mockingbird is used as a symbol for the Black farmworker Robinson, who was innocent and harmed no one, yet was shot. The mockingbird also serves as a figure that bridges distances in this exhibition. It appears repeatedly throughout the show.

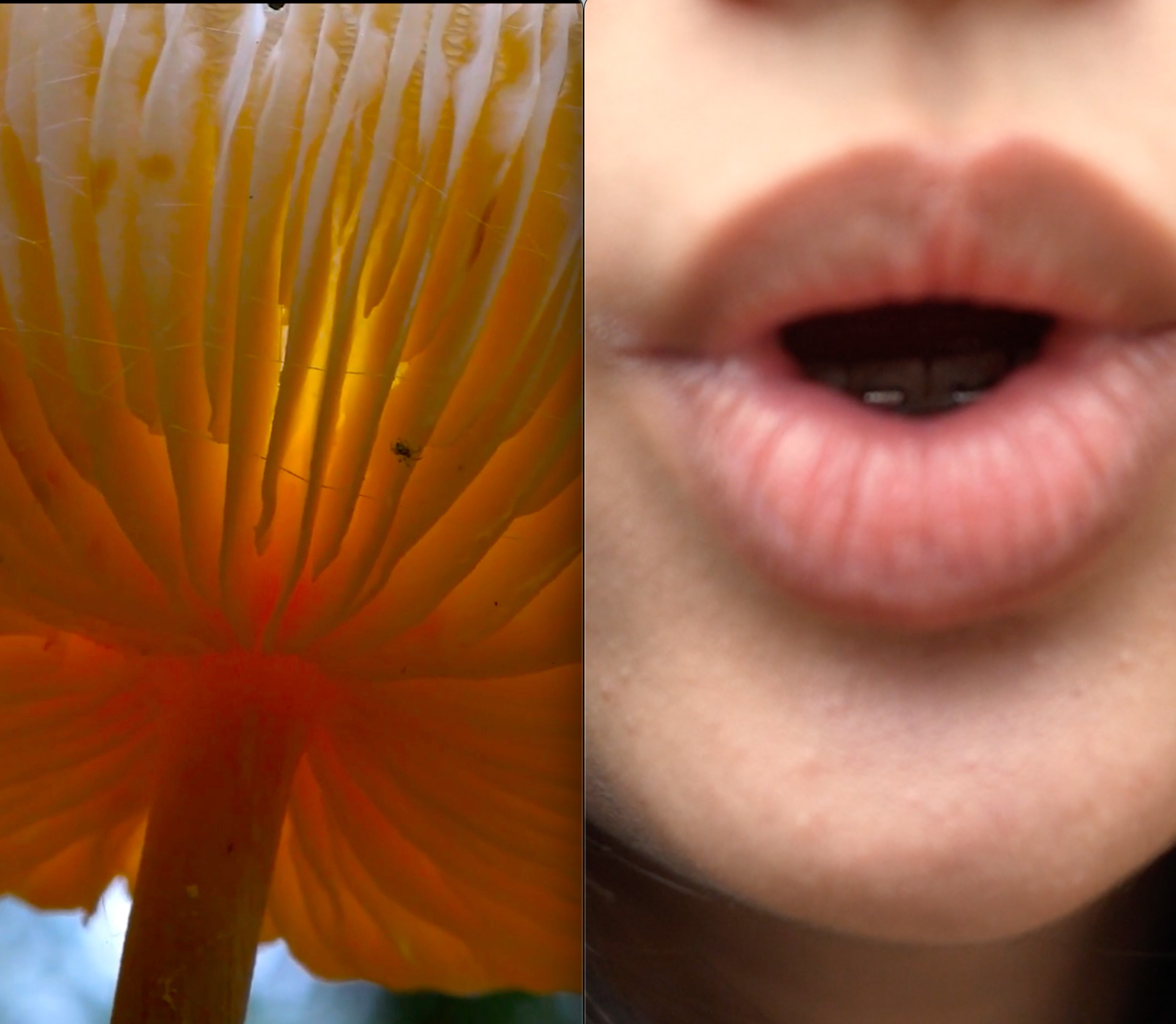

Whistling, listening, passing on, whistling, listening, repeating, understanding? Who learns from whom how to whistle? How is it used in whose everyday life, how in protests, and when does whistling hold potential for resistance? Havîn Al-Sîndy uses various tools to involve everyone in the question of communication and knowledge transfer. The work "Im Nachklang" deals with whistling as a form of nonverbal, coded exchange between children, robots, fungi, and birds. Through interactive AI sculptures, a cacophony of narrative and expression is created, simultaneously questioning social norms and power structures, similar to Harper Lee’s literary characters who reveal the superficial judgments and moral failings of American society.

Ayham Majid Agha transforms his own texts in the style of other poets, and this translation becomes an ornament. These are subtly integrated between the spaces, thus bridging the silence between the versions. The silence in historiography, where certain stories are suppressed, finds no place in Loos’ concept of clear, simple, and unified narratives in architecture. In the exhibition, his poems will be presented among the works that visually and thematically address these contrasts.