Galeria Dawid Radziszewski curated by Reilly Davidson

„Durée“

www.dawidradziszewski.com

Curator(s):

Artist(s):

- Florence Carr

- Tatjana Danneberg

- Nora Kapfer

- Antonio López

- Mira Mann

- Mickael Marman

- Chaeheun Park

- Phung-Tien Phan

- Olivia van Kuiken

Exhibition text

More

“Durée” derives its main premise from Henri Bergson’s theory of time. According to Bergson, the experience of lived time is achieved primarily through intuition. By “entering into” the object or experience, one is granted access to the “flow of duration,” which cannot be measured or broken up into parts. It is a total and direct flux of heterogeneous states. Durée can be understood through Bergson’s analogy of the arrow’s arc and its essential, continuous path. This movement happens seamlessly through time and space, impossible to break down into parts.

In order to understand the mechanics of the arrow's trajectory, however, one must conceptualize it as a set of distinct positions along its path, each position appearing as a still frame. This lands us in the world of analysis. Most of life is spent in this state, where symbols, images, and language are used as data to make sense of the largely disordered world. This, in opposition to the intuition-driven world of durée, is the domain of spatialized, or objective time, which can be measured, calculated, and conveyed in solid terms.

A few common nodes emerge and recur in Bergson’s writing. Bergson contends that it is a mistake to assume a word or symbol could ever replace a real thing. However, the undercurrent from which these aspects are swept up remains strong and vital. When this flow is accessed, one emerges from it with a new wealth of understanding. This exhibition presents an overview of nine artists whose work toggles between those two states, of analytical stasis and intuitive movement, durée.

Nora Kapfer’s compositions bear repeating forms that jitter between recognition and illusion. The flower motif is perhaps her most consistent, spreading out across her oeuvre over the past several years. Holding fast to references like fin-de-siècle ornamentalism and American modernist painting, she coordinates placeable shapes alongside fields o f abstraction. With each layer, a new spatial configuration is born. She balances between symbol and gesture, mediator and intuitor.

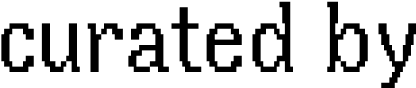

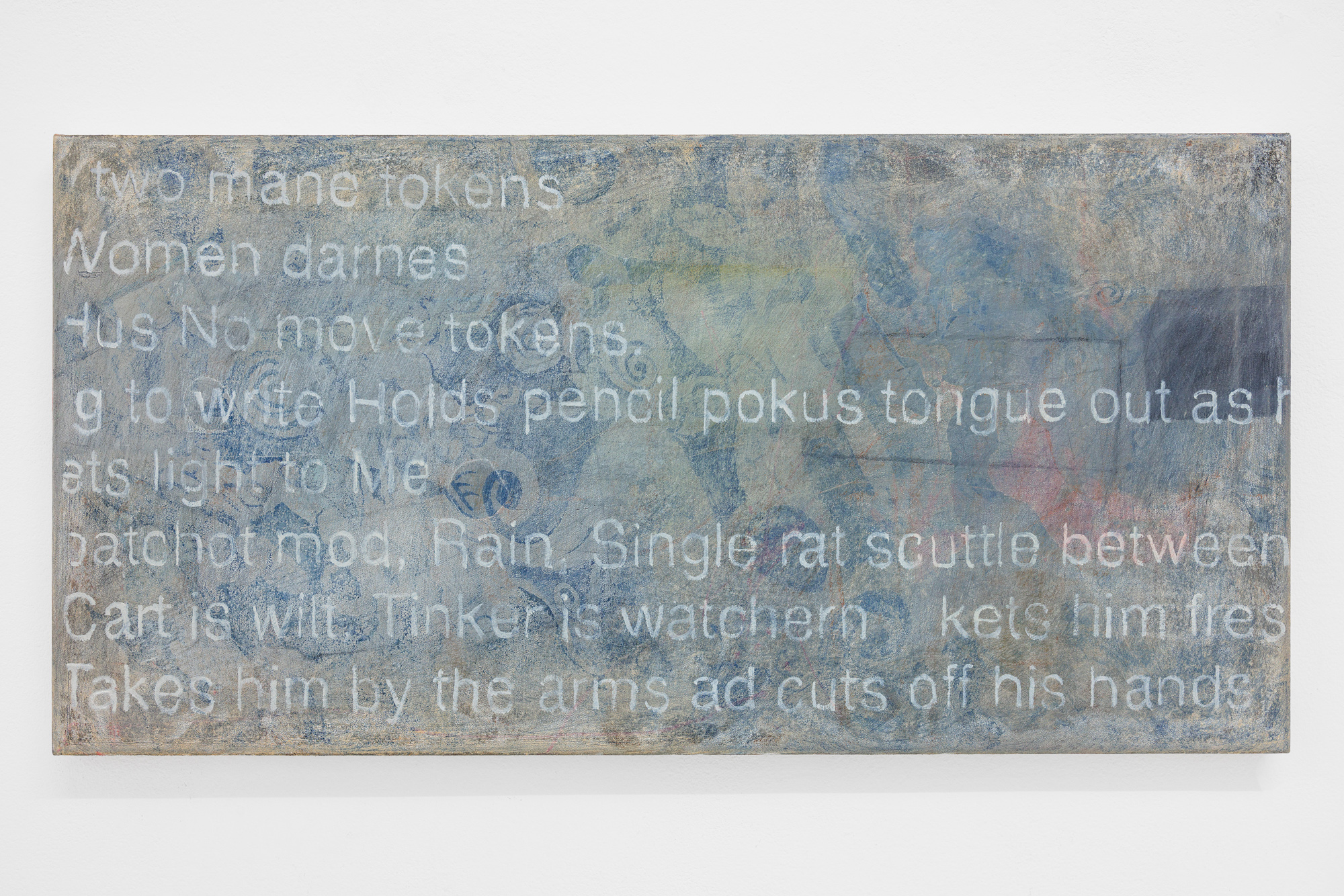

Antonio López similarly imports a range of fragments that, when viewed within his paintings, explode the bounds of semiotics and language. Like Kapfer, his compositions often dissolve into the unrecognizable through collaging and layering, though López ultimately directs the viewer back to semi-recognition in the final image. The artist casts characters that reappear across canvases – from wood panels to silhouetted figures. Along the way, entire zones are buried while other nodes break through the oil strata and reveal themselves to the viewer.

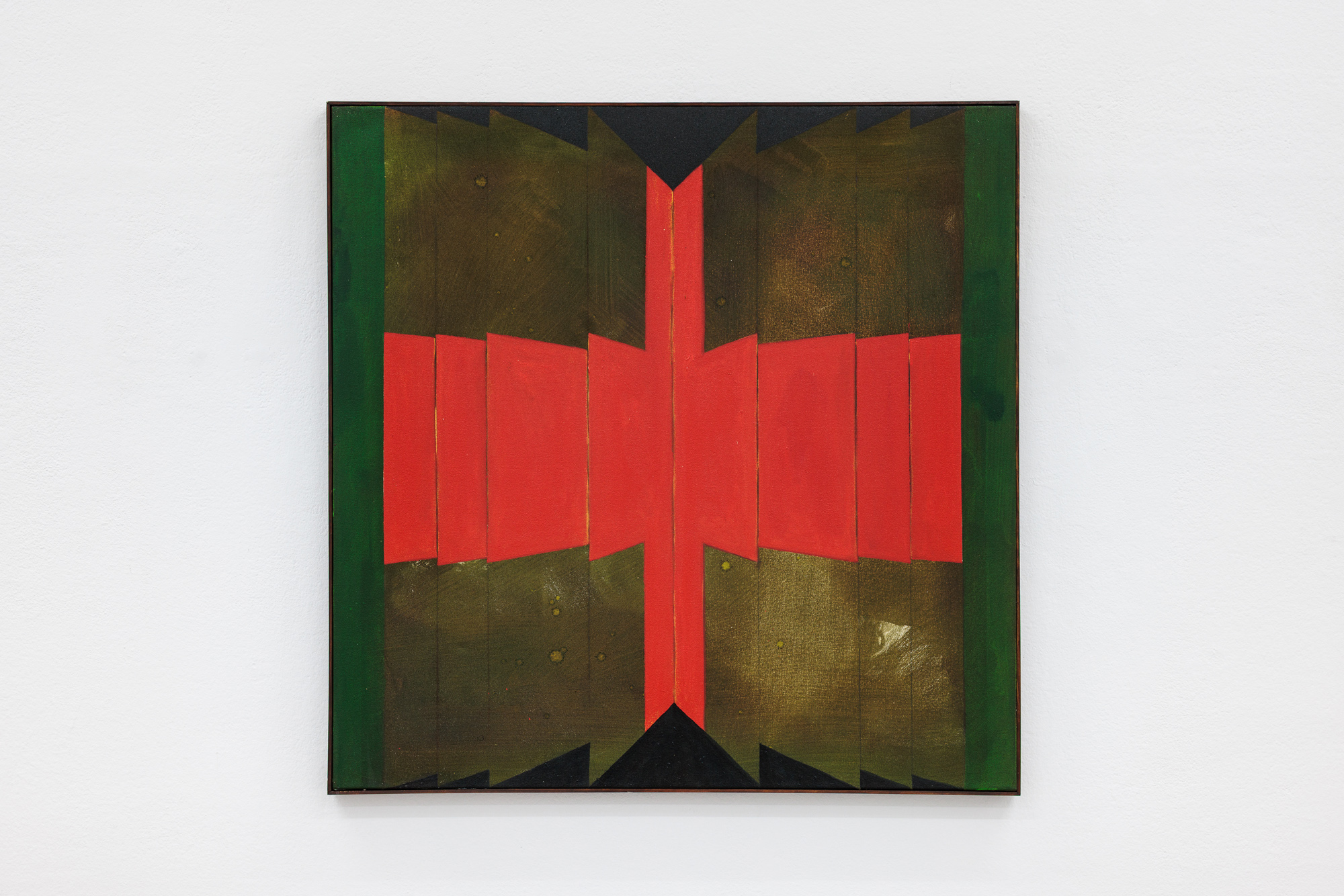

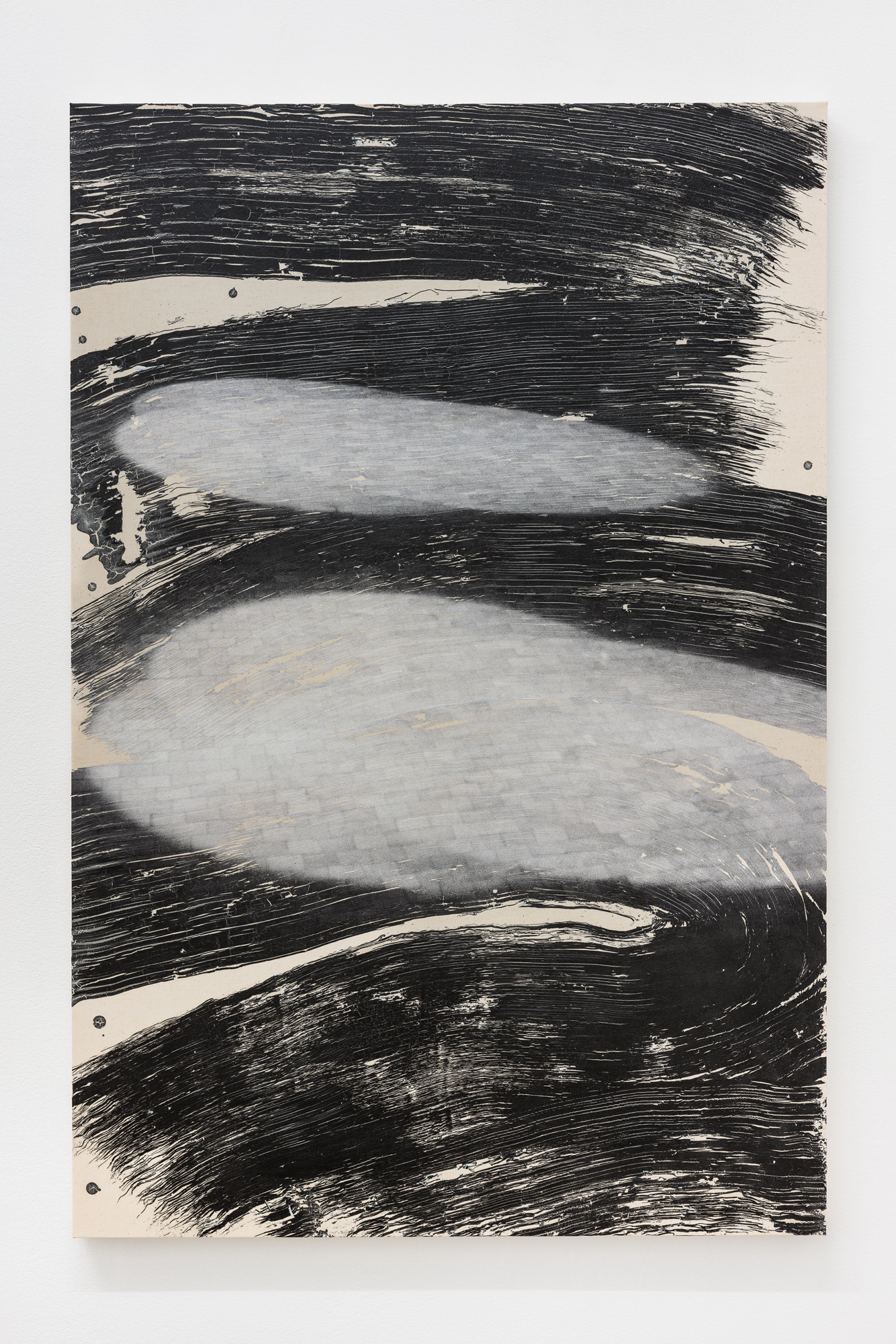

For her part, Chaeheun Park constantly plumbs the archives of online resellers in search of subjects. She approaches her findings like readymades, either referring directly to the source material, or extracting and abstracting elements that draw her attention. In this respect, she primarily attaches her project to a more static appraisal of pictures. Meanwhile, Tatjana Danneberg’s work is rooted in the imaginal realm as she merges specific photographic procedures with painterly interventions. To start, she captures random, everyday encounters with a point-and-shoot camera, freezing spontaneous moments and committing them to the permanence of documentation. These pictures are eventually fractured by the artist’s application of paint, which she employs through a series of intuitive bodily gestures.

Florence Carr considers the associations intrinsic to her chosen materials, though ultimately diverges from them in favor of new conceptual orientations. Along the way, she instills her own subjectivity within the inherited forms, yet manages to torque the final product into something that opens up to a general audience. Carr’s process underscores a preoccupation with the fragility and malleability of perception. A recuperative method is also embraced by Phung-Tien Phan, whose video and sculpture work suspend a stable personhood. She places a peculiar lens over the accumulated objects and catapults them into the realm of contradictions, where facticity is upended. Phan leverages inherited forms, arranging treasures and bric-a-brac that never quite reach a resolution.

There’s an inherent freedom in Mickael Marman’s work, though he holds fast to cultural signifiers and circulated media as a means to both undermine propaganda and present the inherent banality of being. He’s obsessive about paint, and applies it with rigor. Each canvas thus becomes an expressive playground, which the artist floods with pigments and imaginal artifacts. His paintings, when viewed together, bear a sense of ongoingness, as though they belong to a never-ending conversation that the artist is having with his medium.

A collaboration between Phan and Marman arrives in the form of shared materials. The two exchanged objects and tools, then set forth to construct new forms within their respective ecosystems. Their joint departure from methodical comforts marks a foray into the intuitive, as each artist is tasked with exercising their own impulses in unfamiliar territories.

In 1915 Kazimir Malevich created a painting commonly referred to as Red Square, despite its official name being A Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions. His misguiding title is an overt rejection of artists like Jean-François Millet, who championed realism in the previous century. According to Malevich and his Suprematist circle, pure feeling and perceptivity should be favored over meaning and representation in art. Olivia van Kuiken picks up on the plot, embedding this anecdote from the early twentieth century into her own relatively opaque picture plane. Squished Malevich (2025) sees its referent contorted and spun into a new form that appears akin to an open book. Her painting becomes both an homage and response to Malevich, as van Kuiken prods the emptiness of meaning-making. By alluding to such futility, the artist draws upon vacuous symbols and undermines signification.

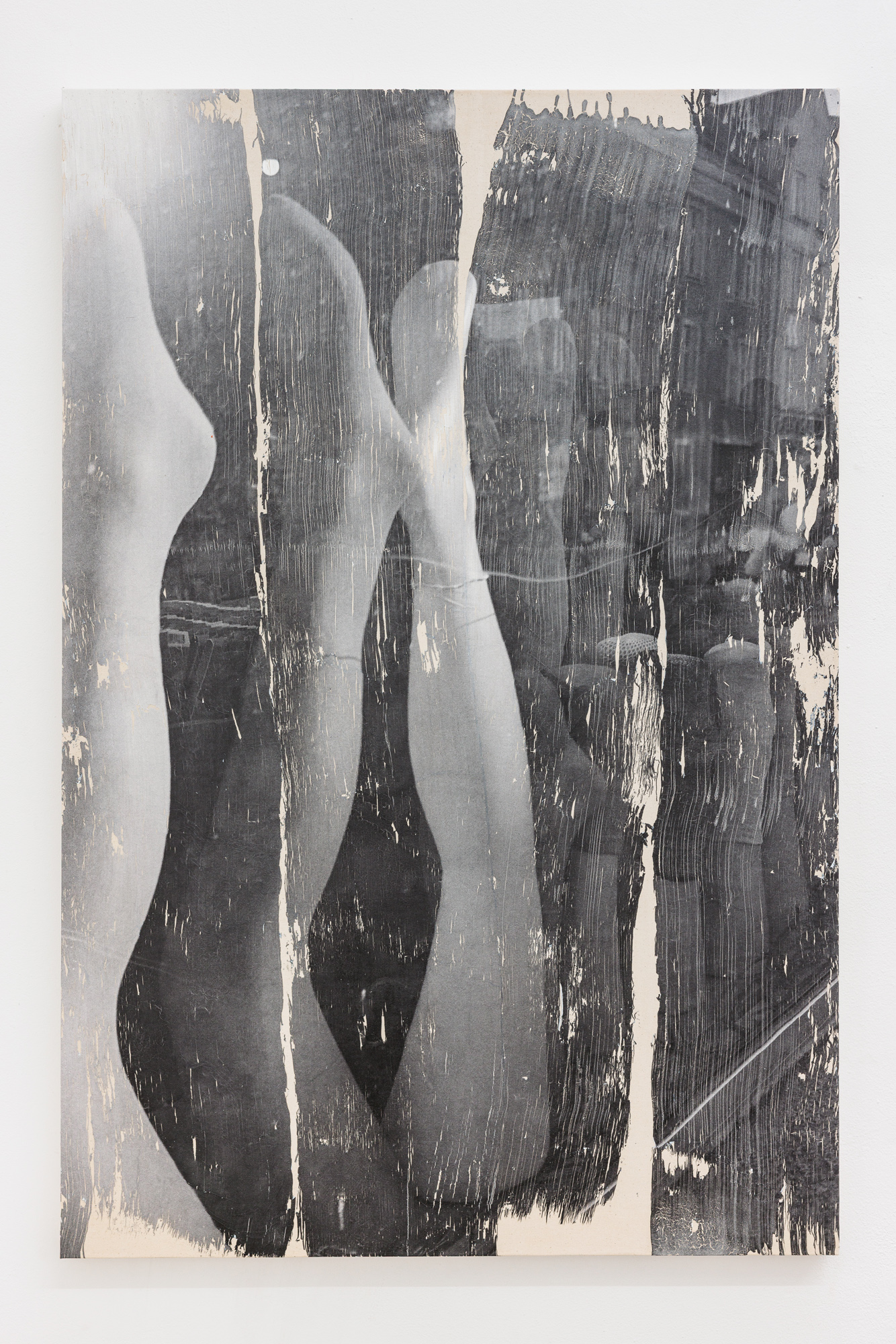

Two new works by Mira Mann extend from their research into the work of Choi Seung-hee (1911-1969), a Korean dancer who combined modern choreography and traditional forms of Asian dance. Choi’s effort spawned a totally unconventional pan-Asian performative method that challenged exoticization and opened up the space for nuanced participation. Mann latches onto this thread, seeking to understand the creation and function of stereotypes. These systems of objectification, which can be broken down into specific emblems and objects, are pondered and exploited by the artist in an effort to get closer to the reality of lived experience.

This exhibition thus serves as a platform to draw distinctions between conceptual examination and intuitive flow. A panoply of forms and images converge here, generated through either symbolic and research-oriented strategies or by diving into the infinite stream of durée.