Galerie Martin Janda curated by Asier Mendizabal

„Reroute—Reorient“

www.martinjanda.at

Curator(s):

Asier Mendizabal (1973) is an artist who lives and works in Bilbao and Stockholm, where he is Professor at the Royal Institute of Art. His work was featured in Reina Sofía, Kunstverein Düsseldorf, Culturgest, and Secession as well as the Venice, Sao Paulo and Taipei biennials. An important part of his practice is writing. He was co-initiator of art pedagogy projects Kalostra and JAI.

Artist(s):

-

Roman Ondak More* 1966 in Zilina (SK) lives and works in Bratislava (SK).

-

Mangelos More1921 born in Šid (SRB) 1987 died in Zagreb (HR).

-

Tania Pérez Córdova More1979 born in Mexico City (MX) lives and works in Mexico City (MX).

-

Ciprian Muresan More1977 born in Dej (RO) lives and works in Cluj.

-

Goshka Macuga More1967 born in Warsaw lives and works in London.

Exhibition text

More

Our exhibition Reroute—Reorient is curated by Asier Mendizabal and features works by Goshka Macuga, Mangelos, Ciprian Muresan, Roman Ondak and Tania Pérez Córdova.

When lost, perplexed, or shocked, we feel the need to reorient ourselves. That is the term we use to define the adjustment to a new situation that might have come about after a sudden, unforeseeable or unfathomable change. To reorient, to orient again, refers, of course, to a spatial notion. By re-establishing a cardinal reference (east, north…) as a spatial metaphor, we determine a position relative to our surroundings, but also, to an uncertain present.

This spatial metaphor of adjusting to a compass differs from the way in which contemporary positioning navigation systems deal with being astray. Rerouting, the term popularised by GPS based systems as the corrective action unequivocally determined by data collection, is different from reorienting. It suggests a calculus of all the possible ways, tracks, and paths after a wrong turn, as if they were all simultaneously available and it were only a matter of computational power to identify the right one. Not so much a directional notion that can always be summoned as an aim – as orientation seemed to suggest– but an indiscriminate scanning of all possible bifurcations, of separating lines out of an indistinct mesh.

If we stretched the analogy of this pair to the subsequent global events that have characterised our present as one of incertitude and bewilderment, we would have to admit that the optimistic, technified mode of positioning ourselves suggested in rerouting entails a naturalised ideological worldview, made of pragmatic choices. Or, conversely, that we have lost trust in any valid anchor point towards which to rearrange our efforts, as an imagined trajectory drawn by a line.

Lines as trajectories or vectors, but also as connectors and as borders feature as a recurrent element in the works that thread this exhibition. These are the three main uses for lines in diagrammatic representations: projecting, connecting, and separating. In all cases, they imply the relation between two entities: a given position, and an aim, in a trajectory, two related elements in a connector, or two planes after a cut – the line is the representation of mediation but is never on either side of the dichotomy. A timeline, two connected units or two divided areas imply a diametrical connection between two things and, therefore, a specular relation and a threshold.

Janus, the Roman god of doors and thresholds, is always represented as a double face, looking simultaneously in two opposite directions. Backwards and forwards, inwards and outwards, into the future and into the past. Its constitution is the exact inversion of a mirror. Whereas the reflection of one’s face in a surface creates an inward illusion of introspection, the faces turned outwards in the representations of Janus create an axis at the point in which each gaze cannot encounter the other. The threshold is always elusive. Irrepresentable. Maybe this is why Janus also presided the dealings between war and peace.

Goshka Macuga’s International Institute of Intellectual Co-operation (2016) features a group of portraits connected by rods which draw a diagrammatic relation between them. It remains unclear whether the lines link or separate these faces, but as in a multifaceted Janus, they cannot look at each other. The title of the series and the subtitle for this particular configuration (End of God: Madame Blavatsky, Giovanni Pico Della Mirandola, Monster of Frankenstein, Rabindranath Tagore, Charles Darwin) directs the reading towards the historical recurrence of the utopian notion by which cultural exchanges and relations would necessarily foster a peaceful stability. The ambivalence of the function of the connecting rods, simultaneously linking and separating the portraits, suggests an analogue impossibility as the axis/threshold in the Janus head.

When Ciprian Muresan overlaps several partial casts of busts (Untitled (Portrait), 2021), the multifaceted structure of Macuga’s constellation seems to condense in an equivalent paradox. This method of overlapping is recurrent in Muresan’s work, most notably in his accumulation of lines which, as in a palimpsest, form simultaneous layers of what in its original form would be linearly organised pages in a book (All the Images from the Complete collection catalogue of S.M.A.K., 2019). It is a spatially paradoxical representation of time, both in its overlapping and transparency, and in its spreading throughout the support generating a surface reminiscent of a map.

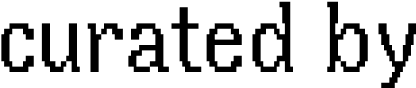

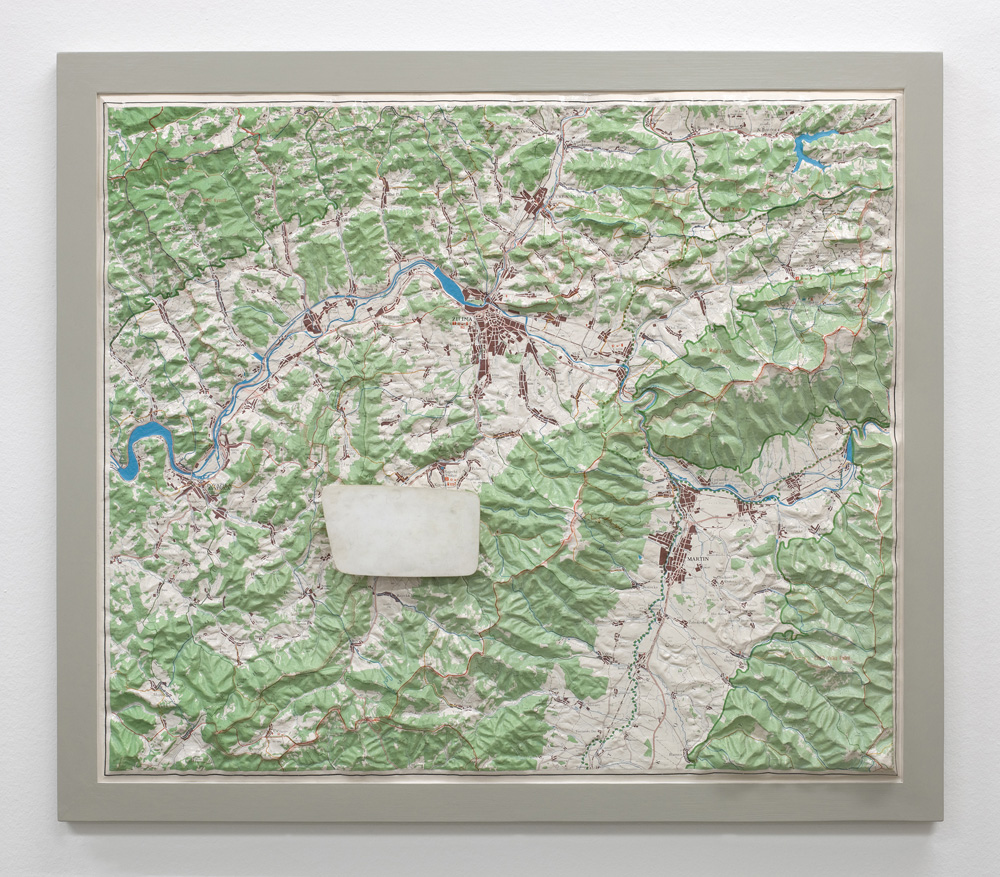

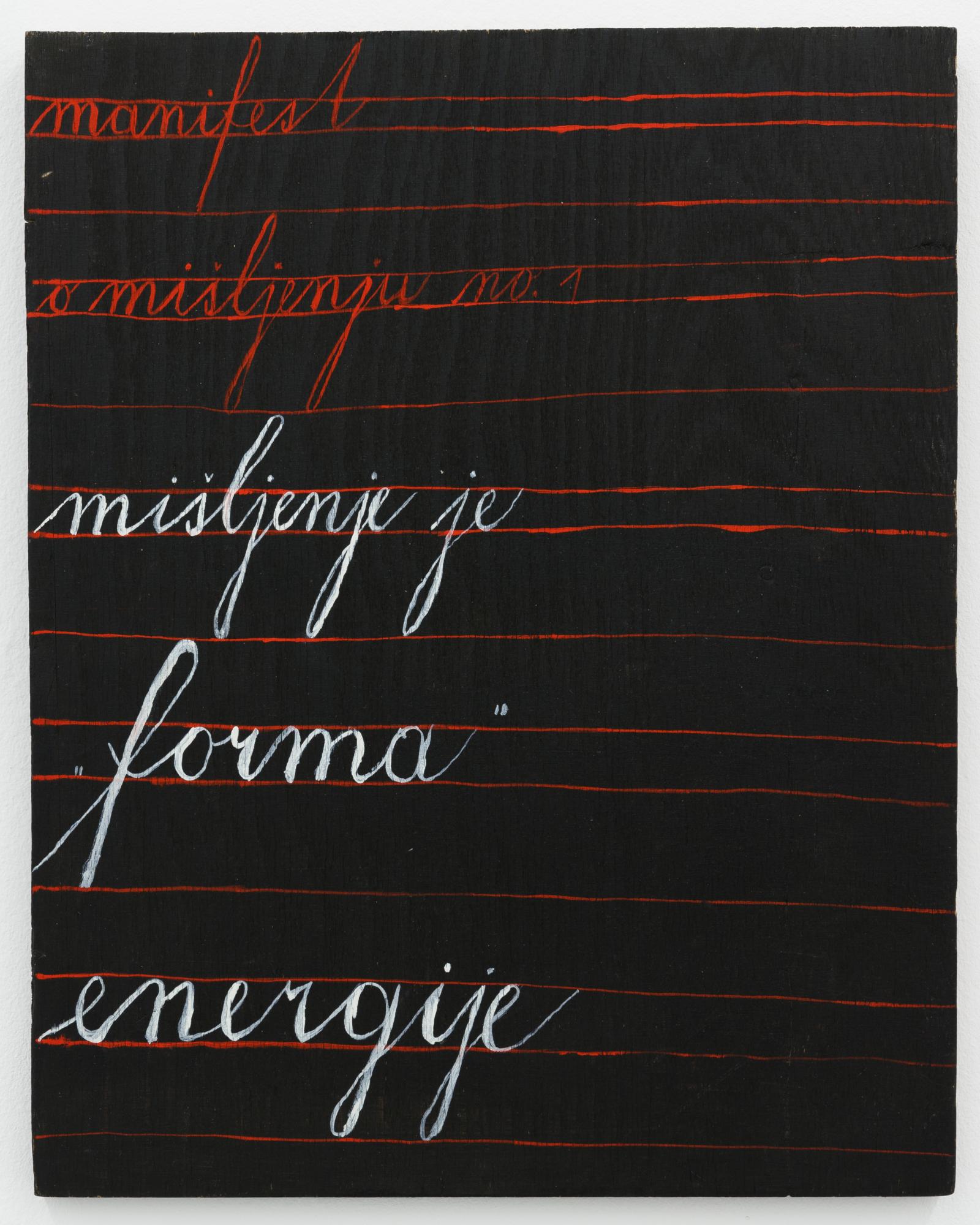

The contour of an absent rear-view mirror, identified in the title of Roman Ondak’s work, Erased Wing Mirror (2013), also denies the reflection of our face, suggesting the impossibility not only of facing ourselves as other, but also of looking back, which is, after all, what rear-view mirrors allow us to do. Placed over a relief map, the cut-out mirror evokes the idea of journey and of borders as inevitably linked to the temporal dimension of travel, and the difficulty to orient ourselves in absence of a historical perspective. Ondak returns to the trope of the mirror, albeit less explicitly, in his new piece Parallel Worlds (2022), in which the two contiguous representations of a globe, where the lines that represent latitude and longitude of the geographic coordinate system are engraved, overlapping the concentric growth lines of the section cut of a tree. The ideal nature of the geographical divisions contrasts with the irreducible material condition of the organic tree, not unlike the way in which Tania Pérez Córdova’s Contour #12 (2021) draws a threshold by pouring bronze into a sand mould of lines which, far from their diagrammatical abstraction, spill out of their borders. The lines of ruled notebooks replicated in all Mangelos’s painted manifestos seem similarly imperfect. Hesitant and contingent, they seem almost incapable of fulfilling their function of straightening the calligraphy into a systematic logic. The cadence of the line that constitutes the handwriting in these works (Hamurabi Manifesto, Energia, Manifesto on Thinking No. 1, all dated between 1971 and 1978) is no less decisive than the abstract template that should have normalised it by subjecting it to the order of the parallel lines.

Asier Mendizabal